How Can We Jump When the Ground Does No Work?

It is relatively common on Physics Forums to see arguments that are effectively similar to the following:

When we jump off the ground, the ground does not move. Because of this, the force from the ground on us does zero total work. Since the force does no work, we cannot gain any kinetic energy. We therefore cannot jump off the ground.

Now, the conclusion here is false. The world high jump record is 2.45 meters, definitely larger than zero. So where did the energy come from? This Insight seeks to clarify this in a fairly accessible way.

Table of Contents

An idealized example

Before jumping off into bipedal mammals competing in the high jump, let us look at an idealized example. This example will help us understand what is going on a little better.

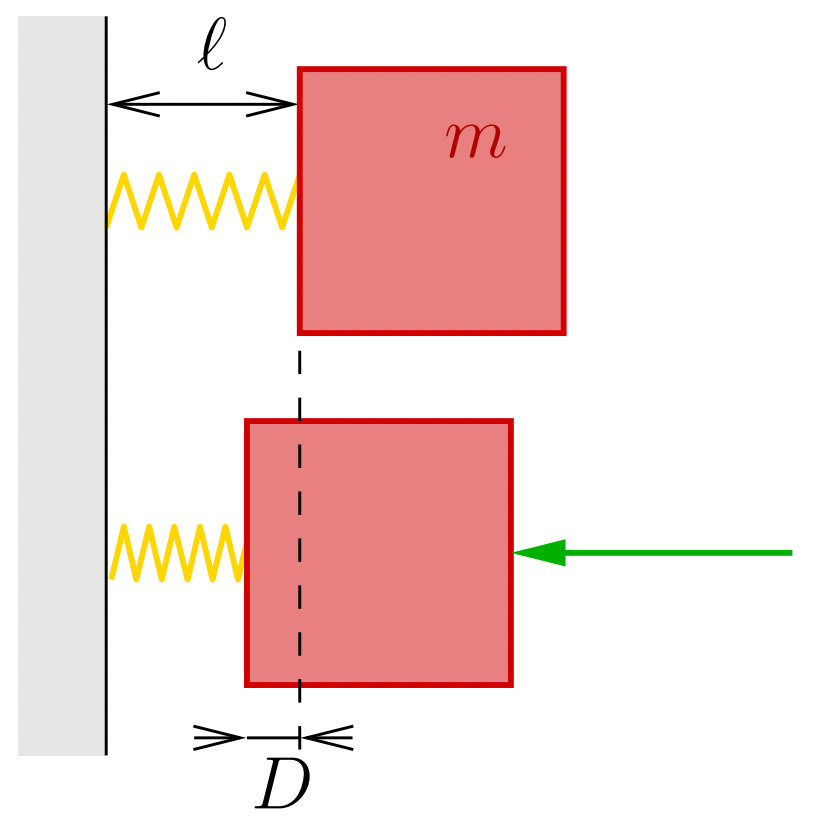

A mass ##m## has an ideal spring of length ##\ell## and spring constant ##k## attached to it. The mass and spring are pressed against a fixed wall such that the spring is compressed by a distance ##D##, see the figure below.

A mass ##m## is attached to a spring of length ##\ell## next to a wall. When pressed towards the wall, the spring compresses by a distance ##D##.

In other words, the mass of the spring is zero, and the force at its ends is given by Hooke’s law. All of this occurs in a horizontal plane, meaning that we do not need to deal with gravity.

Once released, the spring pushes the mass away from the wall. Similar to the jump off the ground, the wall provides no work. By the same reasoning as in our example argument, the mass cannot move away from the wall.

Where is the energy?

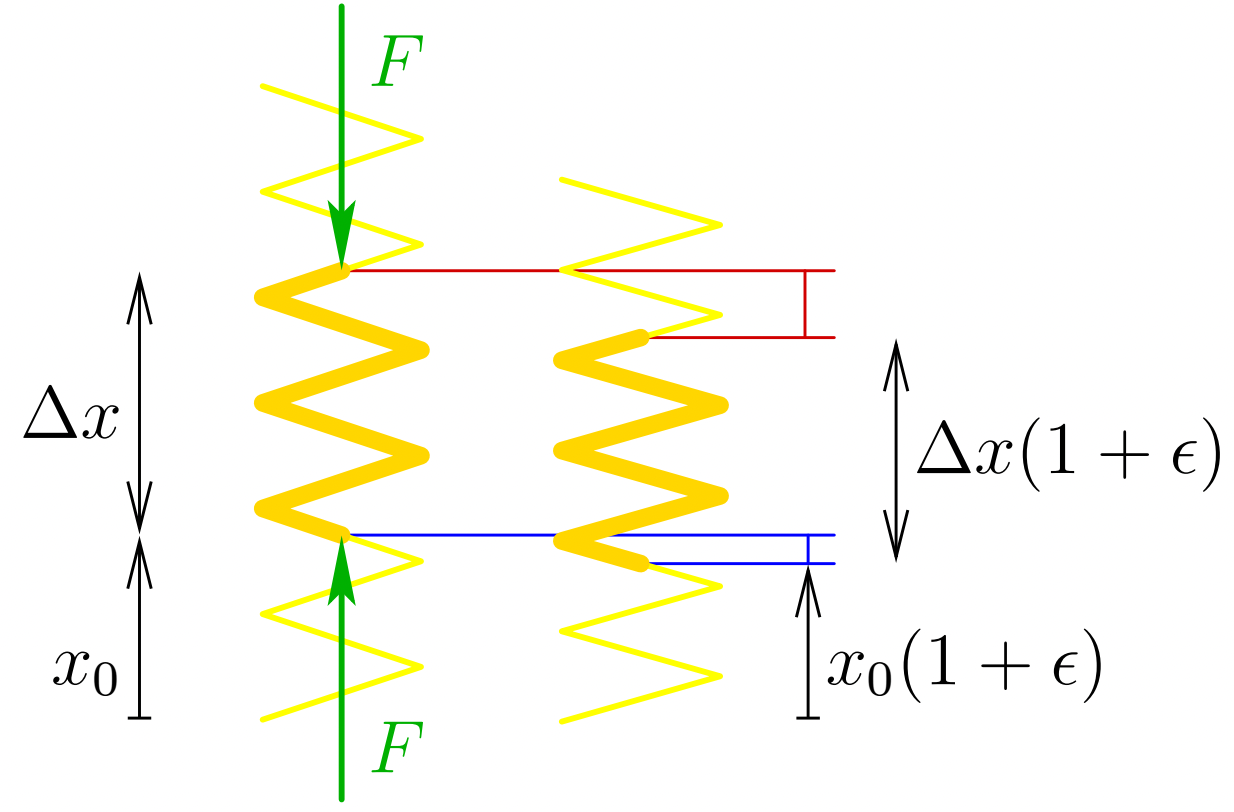

So where does the energy come from? Because the spring will certainly launch the mass away from the wall. To answer this, let us first look at the process of compressing the spring. In particular, we consider a small segment of the spring between the coordinates ##x_0## and ##x_0 + \Delta x## when the spring is relaxed. The compressing force pushing on its ends is ##F = -\kappa \epsilon## by Hooke’s law (see the figure below). Here ##\epsilon## is the strain and ##\kappa = k \ell##.

To compress a spring segment ##\Delta x##, forces equal in magnitude but opposite in direction act on both ends. The displacement at the top of the segment (red) is larger than that at the bottom (blue). Therefore, the upper force does positive work of a larger magnitude than the negative work of the lower force.

Changing the strain by ##d\epsilon##, the lower end of the string segment moves by ##x_0 d\epsilon## and the upper by ##(x_0+\Delta x)d\epsilon##. The total work done on the segment becomes $$dW = F x_0 d\epsilon – F (x_0+\Delta x) d\epsilon = \kappa \epsilon \Delta x \, d\epsilon.$$ Integrating this from no strain to a strain ##\epsilon_0## leads to $$W = \kappa \Delta x\int_0^{\epsilon_0} \epsilon\,d\epsilon = \frac{\kappa\epsilon_0^2}{2} \Delta x.$$ This is the total energy stored in the spring segment at strain ##\epsilon_0##.

That the total energy stored in the spring is $$W = \frac{kd^2}{2}$$, where ##d## is the compression of the spring and ##k = \kappa/\ell## is the spring constant, follows directly from the above.

Energy flux

The discussion above suggests the idea that energy can enter or exit an object and remain as internal energy. This occurs through forces acting on the object performing work. A force ##\vec F## acting on an object over a displacement ##d\vec r## will do a total work of ##\vec F \cdot d\vec r##. In the example above, ##x_0 d\epsilon## replaces ##\vec dr## for the lower end as this is the lower end’s displacement and we work in one dimension. Similarly, we have a directed one-dimensional force ##F## instead of the three-dimensional vector ##\vec F##.

The quantity ##F x_0 d\epsilon = – \kappa \epsilon x_0 d\epsilon## is, therefore, a measure of the amount of energy flowing upward through the spring at position ##x_0## when the strain changes by ##d\epsilon##. When ##\epsilon## is negative, i.e., when the spring is compressed, energy will flow upward if ##d\epsilon## is positive. In other words, when the spring is compressing energy flows left in the spring and right when it is decompressing.

Launching the mass

The spring will decompress during the launch of the mass. The internal energy stored in the spring then flows from the spring into the mass. Denoting the compression of the spring ##D(t)##, we find that $$D(t) = D_0 \cos(\omega t)$$ with ##\omega^2 = \kappa/m\ell## during the launch, where the initial compression is ##D_0##.

The launch time interval is ##0 \leq t \leq \pi/2\omega##. The strain ##\epsilon## is related to ##D## as ##\epsilon = -D/\ell##. We therefore obtain $$\frac{d\epsilon}{dt} = -\frac{D'(t)}{\ell} = \frac{D_0\omega \sin(\omega t)}{\ell}.$$

Consequently, the energy flowing up through the spring at position ##x## is $$\frac{dW}{dt} = -\kappa \epsilon x\, d\epsilon = \kappa \frac{D_0\cos(\omega t)}{\ell} x \frac{D_0\omega \sin(\omega t)}{\ell} = \frac{\kappa D_0^2}{2\ell^2} \omega x\sin(2\omega t).$$

Naturally, this grows linearly with ##x##. As all energy released from the spring flows into the mass, the energy flow gets larger the closer to the mass we get.

Relation to the jumper

A jumper’s legs are by no means an ideal spring. However, the discussion above does give some insight into the issue presented in the beginning:

- The upper body will receive net work from the legs much like the mass received net work from the spring during launch.

- The net work from the ground is zero.

- The energy is provided from internal energy stored in the jumper’s muscles. Just as the energy here was provided from internal energy stored in the spring.

Some differences are also notable:

- Unlike the spring, the jumper’s lower body will have non-zero kinetic energy at the end.

- Energy will also be lost in the form of heat as the efficiency of conversion of internal energy to macroscopic kinetic energy is not 100%.

While the ground does not do work on the jumper, the jumper’s momentum is provided by the force from the ground. This momentum is distributed throughout the jumper’s body by internal forces.

Professor in theoretical astroparticle physics. He did his thesis on phenomenological neutrino physics and is currently also working with different aspects of dark matter as well as physics beyond the Standard Model. Author of “Mathematical Methods for Physics and Engineering” (see Insight “The Birth of a Textbook”). A member at Physics Forums since 2014.

The force results in an equal in magnitude but opposite in direction change in momentum of jumper and earth away from the center mass of earth and jumper. Due to the earth being massive, the change in speed of the earth is extremely tiny, so almost all of energy goes into the jumper.

"

See #20-#22. The misconception that is being addressed is that the ground not doing work on the jumper would prevent kinetic energy buildup. This misconception is solved by showing how internal energy can be released by parts of the body moving at different velocities. Due to the small motion of the Earth (neglected in the Insight), the energy flow into the Earth is small (and amounts to the ground doing negative work on the jumper).

The insight mentions the jumper's lower body doesn't move,

"

No it doesn’t. In fact, the point being made is that the lower body extending (although in the example idealised by a spring) is what gives an energy flow into the body from the energy release in the lower body.

Edit: In particular, the Insight explicity states

“Unlike the spring, the jumper’s lower body will have non-zero kinetic energy at the end.”

The zero energy of the spring results from the spring in the example being an idealised massless spring. This is in order to simplify the considerations but does not affect the main point.

IIRC, enthusiastic fans jumping up and down in unison at stadia routinely register on nearby seismo' sensors…

"

Sure, but as mentioned above that transfer is generally into the ground because the floor is not entirely rigid. I also strongly suspect that most of the energy transfer occurs on the landing *thump* rather than at the jumpoff.

"

( Don't forget the thunderous 'Thumper' trucks used for geo-surveys… )

"

We have also all seen Dune … Thumpers can be very useful when dealing with enormous sandworms.

Edit: We are also completely sweeping the entire issue of using other inertial frames under the carpet. Opening that is an entirely different can of worms…

in classical mechanics, doesn't the earth technically "move"? Equal and opposite sort of thing? It's just that the mass of Earth is so huge in relation to the human that it's negligible?

"

Yes, you are right. We are agreeing to neglect that.

If the spring is not attached to the wall, there is no external force to the spring+mass system so its momentum is conserved.

"

It does not need to be physically fixed to the wall to compress the spring.

Wouldn't the explanation be simpler with a spring that is not attached to the wall (so no oscillation)?

"

The spring is not attached to the wall for this very reason. I might have made it clearer in the first image though. Also note that I have been careful to only discuss the launch up to the time when the spring is back to its unloaded length.

The spring is not being de-coupled from the wall entirely. It is still prevented from interpenetrating. It can push. But it is detached so that it cannot pull. It is not glued, nailed, screwed or otherwise fastened down.

"

Ok I see it can push but not pull, in that case momentum is not conserved and yes we will not have oscillation.

If the spring is not attached to the wall, there is no external force to the spring+mass system so its momentum is conserved.

"

The spring is not being de-coupled from the wall entirely. It is still prevented from interpenetrating. It can push. But it is detached so that it cannot pull. It is not glued, nailed, screwed or otherwise fastened down.

Sorry, but I don't see how the spring being attached or not to the wall changes anything in this respect.

"

If the spring is not attached to the wall, there is no external force to the spring+mass system so its momentum is conserved.

Nope. From conservation of momentum, the body cant attain substantial momentum because the spring has negligible mass hence it has negligible momentum after the decompression happens.

"

Sorry, but I don't see how the spring being attached or not to the wall changes anything in this respect.

Wouldn't the explanation be simpler with a spring that is not attached to the wall (so no oscillation)?

"

Nope. From conservation of momentum, the body cant attain substantial momentum because the spring has negligible mass hence it has negligible momentum after the decompression happens.

You start with a horizontal spring but in the analysis you refer to "lower end" and energy flowing upward. It may be confusing.

"

I’ll add ”in the figure”