Learn Why Ohm’s Law Is Not a Law

At first, I wanted this title to say “Ohm’s law is not a Law.” But someone else used that phrase in a recent PF thread, and a storm of protest followed. We are talking about the relationship between the Voltage between two points in a circuit and the current between those same two points.

##R=V/I##, or ##V=IR##, or ##I=V/R##

I won’t explicitly talk about inductance capacitance, or AC impedances, although all of those could substitute for ##R## in the following discussion.

Table of Contents

Semantics

Newton’s Second Law can be derived from fundamental symmetries in nature. But Ohm’s law is not derived, it was empirically discovered by Georg Ohm. He found materials that have a linear relationship of voltage to current within a specified range are called “ohmic.” Many useful materials and useful electric devices are non-ohmic.

Beginners often believe that there is great significance in the use of words like “law” or “theory” In physics. Not so. Often it is just an accident of history or a phrase that slides easily off the tongue. It could have been called Ohm’s rule or Ohm’s observation, but it wasn’t.

Underlying Assumptions and Limitations

Really there is only one assumption behind Ohm’s law; linearity. Not in the mathematical sense, but rather a graph of voltage versus current shows an approximately straight line in a given range.

There are always limits to the range even though they may not be explicitly mentioned. For example, at high voltages breakdown and arcing can occur. At high currents, things tend to melt. In the old days, we said that real-world resistance can not be zero. But now we know that superconductors are an exception to that rule. ##R=0## is OK for superconductors.

Students often forget that limits exist. A frequent (and annoying) student question is, “So if ##I=V/R##, what happens when ##R=0##. Haha, LOL.” They think that disproves the “law” and thus diminishes the credibility of science in general. Their logic is false.

Ohm’s law Has Several Forms

##I=V/R## may be the most familiar form of Ohm’s law, but it is far from the only one.

- In AC analysis, we use ##\bar V=\bar I\bar Z##, where ##\bar V##, ##\bar I## and ##\bar Z## are all complex vectors. ##\bar Z## is the complex impedance that can describe combinations of resistance, inductance, and capacitance, without differential equations. See PF Insights AC Power Analysis, Part 1 Basics.

- ##\overrightarrow E=\rho \overrightarrow J## is the continuous form of Ohm’s law. where ##\overrightarrow E## is the electric field vector with units of volts per meter (analogous to ##V## of Ohm’s law which has units of volts), ##\overrightarrow J## is the current density vector with units of amperes per unit area (analogous to ##I## of Ohm’s law which has units of amperes), and ##\rho## is the resistivity with units of ohm·meters. Use this form to model currents in 3-dimensional space.

- If an external ##B##-field is present and the conductor is not at rest but moving at velocity ##v##, then we use: ##(\overrightarrow E + v \times \overrightarrow B)=\rho \overrightarrow J##

- There are also variants of Ohm’s law for 2 D sheets, for magnetic circuits (Hopkinson’s Law), Frick’s Law for diffusion-dominated cases, and for semiconductors.

Someone on PF once said that one form was the only “true” Ohm’s law. I disagree. All the forms are useful in different contexts. We can honor Georg Ohm by using his name to cover all the variants, even if he didn’t personally invent all of them.

Real-Life Example, A Solar Panel

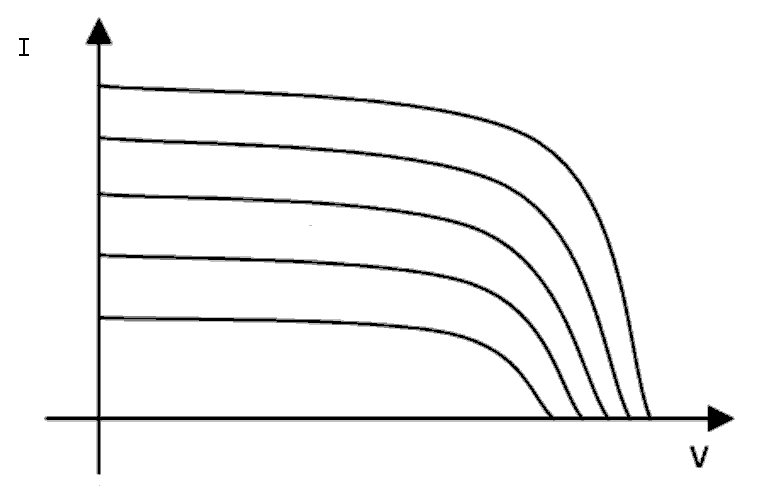

A solar panel is a real-life device. Below, we see a family of curves showing the Voltage V versus current I relationship of a solar panel. Each curve represents a different value of solar intensity. As you can see, the curves range from nearly an ideal voltage source (vertical) to a nearly ideal current source (horizontal), to everything in between.

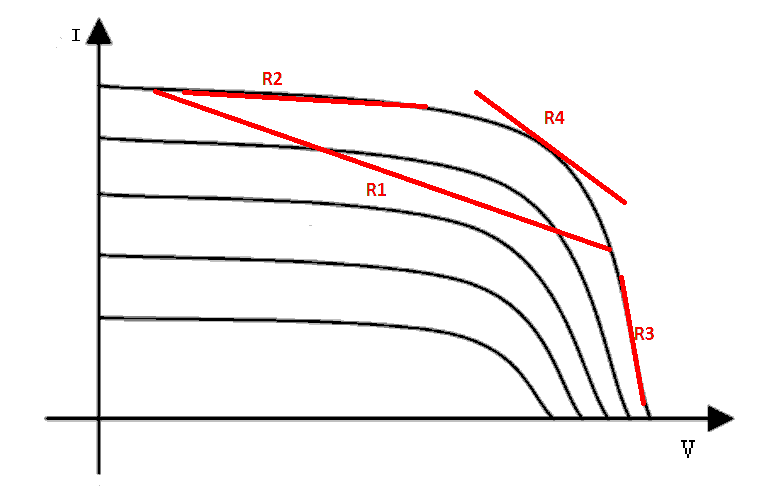

We can draw straight line segments to define the average resistance over a particular range, like R1, R2 or R3. As you can see, the panel ranges from nearly an ideal voltage source to a nearly ideal current source, to everything in between. R4 shows a resistance defined by the tangent to the curve at one particular point. I call R4 the resistance linearized about a point on the curve.

We could use these resistances, plus Thevanin’s Equivalent voltage ##V_{thev}## to model the solar panel in a circuit to be solved using Ohm’s law. (##V_{thev}## is the place where the straight line intercepts the ##V## axis or where ##I=0##).

Arbitrary Numbers of Arbitrary Electric Devices

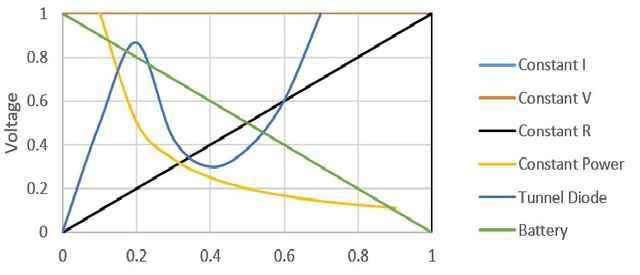

When we go beyond a simple resistor made of some material with a linear V-I relationship, we find that very many real-world devices are non-linear. For example, the constant power device (yellow) and the tunnel diode device (blue) curves are seen below. There are no physical constraints on the shape of a V-I relationship other than that both V and I must be finite. Even a multi-valued curve that loops back on itself violates no physical law.

Students in elementary circuits courses often learn only about the constant R (i.e. the resistor) element, plus L and C. Other kinds of nonlinear circuit devices may not even be mentioned.

At first glance, you might say that Ohm’s law doesn’t apply to nonlinear devices, but that’s not true. Suppose we had a circuit containing a solar panel, a constant power, and a tunnel diode. A student using paper and pencil could not be asked to solve such a circuit, so courses that limit themselves to paper and pencil methods do not cover nonlinear elements. But using computers, there is a relatively simple method:

- Guess an initial V and I point along the curve for each device.

- Find the linearized resistance (analogous to R4) for each device at the V and I guess point.

- Solve the linearized circuit using Ohm’s law, calculating new values for each V and I.

- Use the calculated V and I as the new guess and return to step 2.

An iteration like that is very easy to perform with a computer. It isn’t guaranteed to succeed, but when it does succeed, after several passes through steps 2 and 3, it will calculate values for V and I that simultaneously satisfy the relationships of all linear and nonlinear elements in the circuit. It is routine in power grid analysis to solve circuits with a million or more diverse nonlinear elements. Thus, even when modeling devices that don’t seem to obey Ohm’s law, that we can make productive use of Ohm’s law nevertheless. I’ll say it again using stronger words. Ohm’s law cannot be violated in real life; rather it can be adapted to nearly all real-life situations in electric circuits.

Ohm’s law is not always a complete description of electrical devices, but Ohm’s law is almost always a useful tool. Students are advised to learn to think that way. Physicists and engineers seek usefulness and try to leave the truth to philosophers.

Electricity Study Levels

One can study and explain electricity at (at least) 5 levels.

- Quantum Electrodynamics (QED)

- Maxwell’s Equations

- The Drude Model

- Circuit Analysis

- RF circuits and propagation

In this article, my focus was circuit analysis. One of the standard assumptions for circuit analysis is that Kirchoffs laws apply instantaneously to the entire circuit. That makes ##V## ##I## and ##R## co-equal partners. None of the three can be said to cause and the other effect. All three apply simultaneously.

Students dissatisfied with Circuit Analysis sometimes yearn for physical explanations and invent false narratives about what happens first and what comes next. If you are such a student, I urge you to study Circuit Analysis first, then follow up with the other levels. If that describes you, I advise that the next step is to abandon circuit analysis, Ohm’s law, and Kirchoff’s laws, and to learn Maxwell’s equation as the next deeper step. Fields, not electron motion are the key to the next deeper step.

—

Thanks to PF regular @Jim Hardy for his assistance.

Dick Mills is a retired analytical power engineer. Power plant training simulators, power system analysis software, fault-tree analysis, nuclear fuel management, process optimization, power grid operations, and the integration of energy markets into operation software, were his fields. All those things were analytical. None of them were hands-on.

Dick has also been an exterminator, a fire fighter, an airplane and glider pilot, a carney, and an active toastmaster.

During the years 2005-2017. Dick lived and cruised full-time aboard the sailing vessel Tarwathie (see my avatar picture). That was very hands on. During that time, Dick became a student of Leonard Susskind and a physics buff. Dick’s blog (no longer active) is at dickandlibby.blogspot.com, there are more than 2700 articles on that blog relating the the cruising life.

Therefore, IMO we should all thank our lucky stars for the accident that Ohm's Law is useful at all.It's just as well we decided to use metals and a small range of temperatures to start off our EE research.

Students wouldn't ask that dumb question if they understood that Ohm's Law only applies to a limited region. I don't believe that their teachers understand that. I suspect that the teacher's teachers don't understand that.Agreed: There are thousands of teachers who would say that "Ohm's Law tells us that the Resistance of the component is V/I". You read it everywhere. Why don't they just call it Ohm's Formula and save all that angst? Would they say "Newton's Law is the SUVAT equations"? Funnily enough, no.

I don't know, what you mean. Electric conductivity is a typical transport coefficient, describing the response of the medium to a small perturbation around equilibrium (in this case by a weak electromagnetic field). It's restricted to weak fields in order to stay in the linear-response regime. Of course, it has a range of validity, as has any physical law (except the ones we call "fundamental", because we don't know the validity ranges yet ;-)).I think you ignored the following paragraph from the article that inspired me to write the article in the first place.

Students often forget that limits exist. A frequent (and annoying) student question is, “So if I=V/R, what happens when R=0. Ha ha, LOL.” They think that disproves the “law” and thus diminishes the credibility of science in general. Their logic is false.Students wouldn't ask that dumb question if they understood that Ohm's Law only applies to a limited region. I don't believe that their teachers understand that. I suspect that the teacher's teachers don't understand that. In basic electricity Ohm's Law is being taught as absolutely true as if it had a foundation like the principle of least action underlying Newton's Laws of Motion. Somehow, the message that limited ranges are obvious is not getting passed down the ladder. Perhaps is is related to the fact that conduction in bulk materials requires quantum effects to accurately describe and that is just too difficult for most students and most teachers. That is what this article tried to address.

Even grad students and profs could stand a reminder and a moment of reflection on the fact that there is not physical principle that says that there has to be any wide region where voltage and current are linearly proportional. It could have been nonlinear all the way. If that were true, then simple algebra could not have been used to analyze simple circuits, and the evolution of electricity, electronics and computers in the 20th century would have taken significantly longer. If computers had been delayed, so would all of science. Therefore, IMO we should all thank our lucky stars for the accident that Ohm's Law is useful at all.

We are so used to using Batteries, which are essentially Voltage Sources, that it is hard to avoid think of Voltage as the senior member of the VI pair.Try thinking of a superconducting loop with a magnetically induced current. No voltage in the loop before or after the current is induced.

We have disagreed before on the topic of teaching electricity. I think that we should stick to the 3 valid levels, QED, Maxwells, and Circuit Analysis (CA) [including Kirchoff's laws]. One of the key assumptions of CA is

For Voltage to start before Current, explicitly violates this assumption. That's OK in Maxwell's equations, but we should not mention it within the context of using CA. That is not helping students of CA, it is feeding them contradictory and confusing information.

We are so used to using Batteries, which are essentially Voltage Sources, that it is hard to avoid think of Voltage as the senior member of the VI pair.I would agree. One thing worth noting is that a battery can be produced for constant current as well. A short across the terminals results in the off state, or no load. But losses would be greater than an open voltage source. So primary cells have been built for constant voltage operation for over a century.

Nuclear fission batteries have been produced, searching for them using "nucell" will give details. These nuclear cells are not only current sources, but a.c. instead dc. An a.c. current source battery, that is different. Apparently nuclear cells function better as a.c. current sources. They use fissionable material, so I won't hold my breath waiting for them to be available to the general public.

Claude

Yesz it is. I & V generally h ave a circular relation. Either can come first & produce the other.We are so used to using Batteries, which are essentially Voltage Sources, that it is hard to avoid think of Voltage as the senior member of the VI pair.

Isn't that just a chicken and egg argument for describing a 'relationship' between two variables?Yesz it is. I & V generally h ave a circular relation. Either can come first & produce the other.

…and we can think about the meaning of the form: V=I*R.

We are using this form to find the "voltage drop" caused by a current I that goes through the resistor R.

However, is it – physically spoken – correct to say that the current I is producing a voltage V across the resistor R ?

(Because an electrical field within the resistive body is a precondition for a current I, is it not?)Yes it is physically correct to say that current I produces voltage V in a resistance. It is also correct that a voltage V places across resistance results in current I.

Either one can give rise to the other.

No, an electric field across the resistance is not necessary for current to commence. A switch is closed, a battery has an E field due to redox chemical reaction. Charges move through the cables towards the resistor. Current is already commenced by battery redox. When the charges reach the resistance, they continue into the body but incur collusions between electrons & lattice ions. This results in e lectrons droppii g from conduction band down to valence band. Polarization occurs with photon emission. When current is in a resistance it gets warm from this energy conversion. The E field across the resistor happens when charges emitted from the battery arrive. Positive battery terminal attracts electrons from cable. An electron vacating its parent atom leaves a positive ion behind or hole if you prefer. The atom next in line emits an electron towards this hole. Reverse happens at negative battery terminal. The charges & the associated E field arrive at the resistor. Current already is established, as the charges are in motion before the resistor receives them. Charges proceed through the resistor colliding with lattice ions resulting in polarization & photon emission. Polarized charges have an E field, & the line integral of said E field over the distance is the voltage drop.

At equilibrium the equation J = sigma*E, or E = rho*J, which is Ohm's law in 3 dimensions. I will elaborate if needed.

Claude

Yes, if it's an applied voltage. A voltage drop (symbol V) occurs when current passes through the resistor.

Conversely, with a voltage source, EMF (symbol E) produces the current that passes through the resistor.Isn't that just a chicken and egg argument for describing a 'relationship' between two variables?

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5595672, member: 260864"]I don't know, what you mean. Electric conductivity is a typical transport coefficient, describing the response of the medium to a small perturbation around equilibrium (in this case by a weak electromagnetic field). It's restricted to weak fields in order to stay in the linear-response regime. Of course, it has a range of validity, as has any physical law (except the ones we call "fundamental", because we don't know the validity ranges yet ;-)).”I just meant that your wording and representation takes it to a higher level of understanding and familiarity. Of course the equation is correct – but it doesn't pretend to be a Law. By the time one gets to the level that you are using to describe what happens, I doubt that one would bring in the term Law.But I guess this will never lie down as it falls within the overlap between higher level Physics and down to Earth practicalities; the two have different agendas.

[QUOTE="sophiecentaur, post: 5594992, member: 199289"]That's ramping it up a bit for a number of the audience, I think. But also, if σ changes with some other variable, the relationship breaks down so any 'Law' has hit the rails. A Law that's worth its salt will involve all the relevant variables – Ohm's law, when stated fully, fits that requirement.”I don't know, what you mean. Electric conductivity is a typical transport coefficient, describing the response of the medium to a small perturbation around equilibrium (in this case by a weak electromagnetic field). It's restricted to weak fields in order to stay in the linear-response regime. Of course, it has a range of validity, as has any physical law (except the ones we call "fundamental", because we don't know the validity ranges yet ;-)).

[QUOTE="anorlunda, post: 5594987, member: 455902"]That's true for the specialized case of a linear and uniform mediums. The article addresses the general case of circuits containing any components, linear/nonlinear, active/passive. As the article says, you can always linearize about a point, define R=V/I, then use linear circuit methods to solve it.”It's true for any medium in the linear-response regime. More completely written out the relation reads$$tilde{vec{j}}(omega,vec{k})=hat{sigma}(omega,vec{k}) tilde{vec{E}}(omega,vec{k}),$$where we have Fourier-transformed fields in the frequency-wave-number domain, and ##hat{sigma}## is a complex-valued symmetric 2nd-rank tensor obeying the analytic structure in the complex ##omega## plane such that it is a retarded propagator. If you have "active" elements and non-linearities, you have to extend the approximation beyond the linear-response level, as far as I know.

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5594977, member: 260864"]Ohm's Law is derived from many-body theory. It's defining a typical transport coefficient in the sense of linear-response theory. It's the "answer" of the medium to applying an electromagnetic field, and defines the electric conductivity in terms of the induced current, ##vec{j}=sigma vec{E}##, where in general ##sigma## is a tensor and depends on the frequency of the applied field. So Ohm's Law is a derived law and has its limit of validity (particularly the strength of the electromagnetic field must not be too large in order to stay in the regime of linear-response theory).”That's ramping it up a bit for a number of the audience, I think. But also, if σ changes with some other variable, the relationship breaks down so any 'Law' has hit the rails. A Law that's worth its salt will involve all the relevant variables – Ohm's law, when stated fully, fits that requirement.

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5594977, member: 260864"]Ohm's Law is derived from many-body theory. It's defining a typical transport coefficient in the sense of linear-response theory. It's the "answer" of the medium to applying an electromagnetic field, and defines the electric conductivity in terms of the induced current, ##vec{j}=sigma vec{E}##, where in general ##sigma## is a tensor and depends on the frequency of the applied field. So Ohm's Law is a derived law and has its limit of validity (particularly the strength of the electromagnetic field must not be too large in order to stay in the regime of linear-response theory).”That's true for the specialized case of a linear and uniform mediums. The article addresses the general case of circuits containing any components, linear/nonlinear, active/passive. As the article says, you can always linearize about a point, define R=V/I, then use linear circuit methods to solve it.

[QUOTE="anorlunda, post: 5594970, member: 455902"]I view the definition of R as the ratio of V and I. As a definition, it can't be violated by definition (pun intended :wink:)”I wholeheartedly agree. It's a formula / definition and says nothing about whether or not Ohm's law happens to apply to what's connected to the terminals on the 'black box' we're examining. R could change, or not as V,I or T changes. If it doesn't happen to change then the component is not following Ohm's Law. But one calculation wouldn't tell you one way or the other.This puts me in mind of the SUVAT equations with which we learned to calculate motion under constant acceleration. We don't refer to them them as 'Laws' of motion and we wouldn't dream of suggesting that a measurement of the change in velocity of an object in a given time would be the same under all conditions. But somehow, R=V/I is referred to as Ohm's Law. Teachers and lecturers can be very sloppy about these things. Aamof, I don't remember the constant acceleration thing being emphasised to me in SUVAT learning days, either. They just drew a V/t triangle and did some calculations. It left me uneasy for quite a long while. But teenagers feel 'uneasy' about a lot of things so it was actually the last of my worries.

Ohm's Law is derived from many-body theory. It's defining a typical transport coefficient in the sense of linear-response theory. It's the "answer" of the medium to applying an electromagnetic field, and defines the electric conductivity in terms of the induced current, ##vec{j}=sigma vec{E}##, where in general ##sigma## is a tensor and depends on the frequency of the applied field. So Ohm's Law is a derived law and has its limit of validity (particularly the strength of the electromagnetic field must not be too large in order to stay in the regime of linear-response theory).

There are no rigid rules in science about the use of words like law, rule, theory, etc, so we are free to disagree I view the definition of R as the ratio of V and I. As a definition, it can't be violated by definition (pun intended :wink:)Newton's Laws and the conservation laws are all derivable from the fundamental symmetries of nature. I resist the idea of making Ohms Law comparable with those. But if you want to call it a law, go ahead and knock yourself out. But don't complain if I prefer different words.

[QUOTE="anorlunda, post: 5557225, member: 455902"]anorlunda submitted a new PF Insights postOhm's Law Mellow Continue reading the Original PF Insights Post.“I disagree to the general Idea that Ohm's Law is not a law, yet I strongly support the importance of this issue which I think boils down to the very basics philosophy of what is a physical law, what are the therms under which it consider violated.Following the article spirit, I would recommend title like: Ohm's hypothesis or even better – Ohm's convention.I understood the solar device is given in order to provide real example for violation of ohm's law. But it is not. the rectification profiles comes from a diode like element in the equivalent circulate. Up to date there is no system that violates "Ohm's law" . Note for example that Memristor, Thermistor, Warburg element or any constant phase (CPE) or non-CPE do not violates Ohm's law.

Continue reading the Original PF Insights Post.“I disagree to the general Idea that Ohm's Law is not a law, yet I strongly support the importance of this issue which I think boils down to the very basics philosophy of what is a physical law, what are the therms under which it consider violated.Following the article spirit, I would recommend title like: Ohm's hypothesis or even better – Ohm's convention.I understood the solar device is given in order to provide real example for violation of ohm's law. But it is not. the rectification profiles comes from a diode like element in the equivalent circulate. Up to date there is no system that violates "Ohm's law" . Note for example that Memristor, Thermistor, Warburg element or any constant phase (CPE) or non-CPE do not violates Ohm's law.

The article "Ohm's law Mellow" address a very impotent issue, Yet there is no evidence for violation of Ohm's law (within the limit of ohm's law). I think the confusion comes from the fact that text book do not elaborates on the preliminary assumptions under which Ohm's law valid.

The relation ##R=frac{V}{I}## is not Ohm's Law. Rather, it's the definition of ##R##.Ohm's Law is the assertion that over a range of voltages, ##R## is constant.Like all laws, it has limits of validity. There is no such thing as a law with universal limits of validity. Hooke's Law is an example of a law that can be compared to Ohm's Law when teaching this concept of limited validity.

Ohms law is based on an ideal world for students. All conductors have a complex impedance based on frequency, temperature, resistance, inductance and capacitance. These vary depending on how cables are run adjacent to each other, even climatic conditions can come into play etc. It isnt an ideal world, even a straight piece of wire has typically 10mH per metre. The complex impedances in a conductor become significant when switching very high currents quickly.

And in the former, energy is supplied. In the latter, energy is consumed.

Remember, tho', the Voltage is the Energy supply for the charge flow. If you really want a cause and effect, I would say the Voltage causes the current. But in circuits, a voltage somewhere else can cause current to glow which will result in a portion of the supply volts appearing across a resistor. That's K2.

[QUOTE="LvW, post: 5557646, member: 541169"]However, is it… correct to say that the current I is producing a voltage V across the resistor R ?”Yes, if it's an applied voltage. A voltage drop (symbol V) occurs when current passes through the resistor.Conversely, with a voltage source, EMF (symbol E) produces a current that passes through the resistor.

[QUOTE="anorlunda, post: 5559084, member: 455902"]It sounds like you didn't read to the end. The article does mention the Dude model as one of five levels at which you can study electricity. It also says that the scope of the article was limited to circuit analysis.”I did see your link to it, but if you read your main article, it left the impression that Ohm's law is not derivable, that it is purely phenomenological. That is what I was objecting to.BTW, the Drude model is not a model for "electricity". It is a model to describe the behavior of conduction electrons. It means that it gives you the definition and the origin of physical quantities such as resistance, current, etc.Zz.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5559026, member: 6230"]However, since the OP discussed the "non-derivable" issue, and did not even mention the Drude model, I consider that to be a significant omission.”It sounds like you didn't read to the end. The article does mention the Dude model as one of five levels at which you can study electricity. It also says that the scope of the article was limited to circuit analysis.

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5559035, member: 260864"]One should also mention that the Drude model is not the final answer but that the "electron theory of metals" is one of the first examples for a degenerate Fermi gas (Sommerfeld model). The model was extended by Sommerfeld, explaining the correct relation between electric and heat conductivity (Wiedemann-Franz law).”Again, we can take this to a million different level of complexities, but this is certainly well beyond the scope of this topic. I mean, just look at Ashcroft and Mermin's text. They started off with the Drude model in Chapter 1, and by Chapter 3, they talked about the "Failures of the Free Electron Model", which was the foundation of the Drude Model.So yes, we can haul this topic into multi-level complexities if we want, but we shouldn't.Zz.

One should also mention that the Drude model is not the final answer but that the "electron theory of metals" is one of the first examples for a degenerate Fermi gas (Sommerfeld model). The model was extended by Sommerfeld, explaining the correct relation between electric and heat conductivity (Wiedemann-Franz law).

[QUOTE="sophiecentaur, post: 5559022, member: 199289"]Yes. But Ohm's Law specifically refers to Metals at a constant temperature, doesn't it? Your point has been ignored by the contributions to this thread.”I beg to differ. By invoking Drude model, I have implicitly invoked temperature dependence.However, to be fair to the OP, Ohm's law in the "practical" sense is often used when the resistance is a constant. Thus, it has already implied that temperature effects are not described within the Ohm's law relationship. I do not see this as being a problem, because this might easily be beyond the scope of this topic.However, since the OP discussed the "non-derivable" issue, and did not even mention the Drude model, I consider that to be a significant omission.Zz.

Well, yes, that's why I wrote this posting :-).

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5559020, member: 260864"]The electric conductivity of course is a function of temperature and chemical potential (for an anisotropic material it's even a tensor).”Yes. But Ohm's Law specifically refers to Metals at a constant temperature, doesn't it? Your point has been ignored by the contributions to this thread.

The electric conductivity of course is a function of temperature and chemical potential (for an anisotropic material it's even a tensor).

It's interesting that, in a thread that is trying to discuss Ohm's Law, no one seems to have mentioned Temperature. Ohm's Law is followed by a conductor when its Resistance (obtained from V/I) is independent of Temperature. "R=V/I" is not Ohms Law, any more than measuring the Stress/Strain characteristic of any old lump of material 'is' Hooke's Law. In circuits, the 'resistive' components are not just designed to follow Ohm's Law (if they are metallic then they will easily do that); they are designed to have a more or less constant resistance over a large temperature range. That is, in fact, a Super Ohm's Law.

There is a major omission in this article.Ohm's law can be derived from the Drude model of conduction in metals. This is the statistical classical model of electron gas in a conductor that connects the current density, the applied electric field, and the conductivity. Unfortunately, this origin is never mentioned in the article.It is from this model that we can see the level of simplification, assumptions, and limitations of Ohm's Law, and thus, can also see when and where it will break down.Zz.

[QUOTE="LvW, post: 5557646, member: 541169"]However, is it – physically spoken – correct to say that the current I is producing a voltage V across the resistor R ?(Because an electrical field within the resistive body is a precondition for a current I, is it not?)”Not true in circuit analysis. That is why I added the last paragraph about 5 levels of study. In Maxwell's equations, we deal with the speed of propagation of fields (speed c in a vacuum). So there we can talk about which came first. In circuit analysis, Kirchoff's laws are assumed to apply instantaneously, so that the V and I appear simultaneously; no first/second. If you want to dig deeper into the physics of what happens first, then abandon circuit analysis, abandon Ohm's law, and use Maxwell's equations. Perhaps I should go back and add that bolded sentence to the article.

[QUOTE="LvW, post: 5557646, member: 541169"]…and we can think about the meaning of the form: V=I*R.We are using this form to find the "voltage drop" caused by a current I that goes through the resistor R.However, is it – physically spoken – correct to say that the current I is producing a voltage V across the resistor R ?(Because an electrical field within the resistive body is a precondition for a current I, is it not?)”We can determine the speed, distance, or rate (MPH/KPH) by knowing 2 of the 3. But, we certainly do not say that the length of the road causes motion of the vehicle. I see it is really no different with ohms law.

Well, it's really semantics. I'd not say that Coulomb's law is "true law of physics" although I prefer the phrase "fundamental law". All physics laws are "true" in the sense that they are well tested by observations and in most cases have a restricted range of validity.That said, I think that Coulomb's Law is, as Ohm's Law, a "derived law" from the fundamental laws of (quantum) electrodynamics. Coulomb's Law is the electrostatic field of a radially symmetric static charge distribution and of course derivable from Maxwell's equations. Ohm's Law is derived from linear-response theory of (quantum) electrodynamics. The electric conductivity is a bona-fide transport coefficient, definable in terms of the Kubo formula. The corresponding correlation function is the em. current-current correlator etc.

There are important distinctions between truly general laws and useful summaries that are technically approximations at best and in some ways more definitions of tautologies. Coulomb's law is a true law of Physics.Ohm's law is more of a definition of Ohmic materials. Ohmic materials obey Ohm's law. That's like saying "It works where it works" without having real predictive power regarding for what materials it will and won't work before the experiment is performed.The ideal gas law is an approximation in a limiting case. In that sense, it is a true law of Physics, at least as much of Galileo's law of falling bodies.

…and we can think about the meaning of the form: V=I*R.We are using this form to find the "voltage drop" caused by a current I that goes through the resitor R.However, is it – physikally spoken – correct to say that the current I is producing a voltage V across the resistor R ?(Because an electrical field within the resistive body is a precondition for a current I, is it not?)

I have actually thought about this a number of times. I look at it from the perspective that ohms is simply a ratio. Sometimes the ratio holds true across a wide range of voltages and currents and with other materials not so much. We can nitpick about this from now until eternity I suppose.

Semantics..Just like Moore's law (which is not a fundamental law of the universe), or evolution theory (which so many have told me is "just a theory").

A question from Reddit”The ideal gas law doesn't apply for real gases. Is the ideal gas law then not a law?”