Permanent Magnets Explained by Magnetic Surface Currents

Table of Contents

Introduction:

The purpose of this Insight is to explain permanent magnets in a way that is in agreement with advanced textbooks on the subject, and that emphasizes the results in these textbooks without requiring nearly the mathematics that these textbooks use. The magnetic fields from a permanent magnet can readily be understood by looking at the magnetic surface currents that result from the magnetization of the magnetic material. The magnetization of a permanent magnet is maintained by the magnetic field from its magnetic surface currents in a self-consistent manner. In this Insight, a couple of rather straightforward calculations will be performed to show how the permanent magnet state results.

(Note: In this Insight, c.g.s. units are being used, but the reader can hopefully adapt the concepts to any units that they may prefer, including SI and MKS. )

Ferromagnetism and magnetic susceptibilities ## \chi ## and ## \chi’ ## for ## H ## and ## B ##:

Ferromagnetism is characterized by a very large response of the magnetization to the applied magnetic field. In many instances, the sample consists of a long cylinder of magnetic material inside a solenoid, and the magnetization ## M ## is measured as a result of the field ## H ## from the solenoid. For linear cases, and even in non-linear cases, the magnetic susceptibility ## \chi ## is defined by the equation ## M=\chi H ##. Because of magnetic surface currents, the magnetic field in the material is not ## H ## but ## B=H+4 \pi M ##. It is the magnetic field ## B ## that causes the magnetization ## M ## to be the value that it is. An alternative magnetic susceptibility ## \chi’ ## can be defined as ## M=\chi’ B ##. Assuming linearity in both cases, these two parameters are related by ## \chi’=\frac{\chi}{1+4 \pi \chi} ##. (This result can be obtained by substituting ## H=\frac{M}{\chi} ## in the equation ## B=H+4 \pi M ## and solving for ## M ## as a function of ## B ##.) There is an inherent non-linearity that occurs in these systems for ## \chi’>\frac{1}{4 \pi} ## as we shall see momentarily.

Brief Description of Magnetic Surface Currents :

To follow the result of the next paragraph, it is necessary to be familiar with the concept of magnetic surface currents. A brief description of them is in order at this point. Magnetic surface currents are the result of gradients in the magnetization vector ## M ##.(The magnetization is a result of magnetic moments being aligned in the same direction at the atomic level. These magnetic moments can be viewed as sub-microscopic current loops all circulating in the same direction=e.g. clockwise. The net effect in bulk material that has uniform magnetization is that these circulating current loops cancel each other, but these aligned magnetic moments will produce a net effect at a surface boundary that results in a surface current that can be of considerable strength=even many, many times stronger than the current of a solenoid.) In the bulk material this results in a magnetic current density ## J_m ## satisfying ## \nabla \times M=\frac{J_m}{c} ##. At surface boundaries, this results (by application of Stokes’ theorem) in a surface current per unit length ## K_m=c M \times \hat{n} ## where ## \hat{n} ## is a unit vector normal to the surface. The magnetic fields from these magnetic surface currents are computed the same way as from any other currents, by using Biot-Savart’s law and/or Ampere’s law. For the case of a cylindrical sample with magnetization along the z-axis, the magnetic surface currents are on the outer surface of the cylinder and are concentric with the current of the solenoid whose ## H ## field is used to create the magnetization in the sample. These magnetic surface currents that result from the magnetization generate their magnetic field which adds to the ## H ## field as we shall compute in the paragraph that follows. It should be noted that the magnetic field ## B ## of a permanent magnet, both inside and outside the permanent magnet, can be computed simply from the magnetic surface currents, assuming the magnetization ## M ## is nearly uniform throughout the magnet.

Computing the geometric series for the applied magnetic field ## H ## plus the resulting magnetization and surface currents that generate additional magnetic field and additional magnetization, etc. :

Consider an unmagnetized cylindrical sample to which a weak field of strength ## H ## is applied by the current in a solenoid. There will necessarily result a magnetization ## M_o=\chi’ H ##, and from this magnetization ## M_o ## results surface current per unit length ## K_{mo}=cM_o##. This surface current per unit length produces a magnetic field ## B_1=4 \pi M_o ##. (Compare with the magnetic field from a solenoid, which has the same geometry as the surface currents around a cylinder: For a solenoid of current with ## n ## turns per unit length, the current per unit length ## K=nI ## and the magnetic field inside the solenoid is ## B= \frac{4 \pi n I}{c} ##). The result is an additional magnetization ## M_1=\chi’ B_1 ##. This magnetization ## M_1 ## in turn has surface current per unit length ## K_{m1}=cM_1 ##, and generates a magnetic field ## B_2=4 \pi M_1 ##. The cycle continues. The result is an infinite geometric series with the magnetic field ## B_{total}=H+B_1+B_2+…=\frac{H}{1-4 \pi \chi’} ## and the magnetization ## M= \frac{\chi’ H}{1-4 \pi \chi’} ##. For ## \chi’>\frac{1}{4 \pi} ## the geometric series diverges and the result will be a large value of magnetization ## M ## that is finite, but nearly saturated. The finite limit of these magnetic systems, which is a saturation of the magnetization ## M ## for large ## B ##, is the inherent non-linearity (with the response of the ## M ## to a strong magnetic field ## B ## being less than linear) in these systems. (In this case, ## \chi’ ## is not constant for large magnetic field ## B ##). For many materials, for which ## \chi’> \frac{1}{4 \pi} ##, it is possible to remove the initial ## H ## with the result being a permanent magnet where the magnetization ## M ## is maintained by the magnetic field ## B ## produced by its magnetic surface currents.

Qualitative understanding of the shape of the hysteresis curve of ## M ## vs. ## H ## considering the magnetic surface currents along with the solenoid current:

The shape of a common hysteresis curve of ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ## H ## can be understood when one considers the magnetic surface currents that arise in the sample. Without the inclusion of the magnetic surface currents, it can be very difficult to make sense of the peculiar shape that occurs. It can be rather puzzling how the applied magnetic field can be reversed and the magnetization remains in the same direction at a very large value. The magnetic surface currents provide the solution to this puzzle: To reverse the direction of magnetization ## M ##, it is necessary to have a current in the solenoid in the opposite direction that is stronger (more current per unit length) than the magnetic surface currents. (The exception to this is the case where no permanent magnet forms. For materials such as soft iron, when the applied magnetic field ## H ## is removed, these materials prefer a solution where many microscopic magnetic domains form with the magnetization of each pointing in various directions with the net result that the overall bulk magnetization ## M ## returns to zero.)

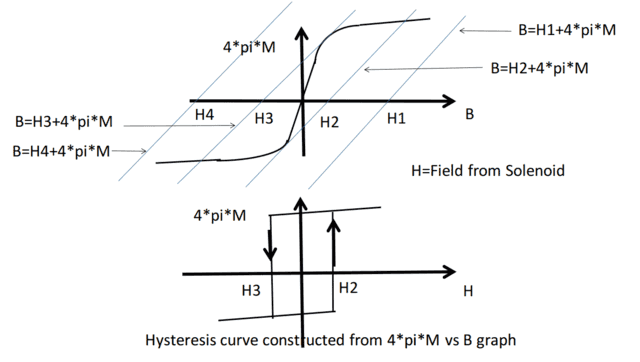

Generating the hysteresis curve of ## M ## vs. ## H ## from the characteristic curve of ## M ## vs. ## B ## for a typical ferromagnetic material:

The hysteresis curve of ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ## H ## can be generated from the more well-behaved characteristic curve of ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ## B ## by overlaying the line ## B=H+4 \pi M ## and allowing ## H ## to vary as is shown in figure 1. The value for ## H ##, (which is proportional to the solenoid current), becomes the x-intercept for the line ## B=H+4 \pi M ## on the graph of ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ##B ##. The intersection of this line with the characteristic curve of ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ## B ## is the operating point from which a pair of values ##H ## and ## M ## can be obtained. As the ## H ## is reversed and becomes negative, eventually the magnetization ## M ## jumps discontinuously from ## M=+M_{sat} ## to ## M=-M_{sat} ## where ## +M_{sat} ## and ## -M_{sat} ## are the saturation levels of the magnetic material. This is all consistent with the qualitative explanation above, that the magnetization reverses its direction once the ## H ## from the solenoid current becomes larger than, (and in the opposite direction of), the magnetic field from the surface currents. Notice also from the graph of ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ## B ## that if ## \chi’=\frac{M}{B}> \frac{1}{4 \pi} ##, (in the linear portion of the ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ## B ## graph), that the line ## B=H+4 \pi M ## for ## H=0 ## will intersect the characteristic curve of ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ## B ## at the saturation values of ##M=+M_{sat} ## and ## M=-M_{sat} ##. This indicates that a permanent magnet will form in one of two states: either the magnetization ## M=+M_{sat} ## or ## M=-M_{sat} ## for the case of applied field ## H=0 ##.

Figure 1.

In Figure 1 above, the hysteresis curve of ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ## H ## is generated from the graph of ## 4 \pi M ## vs. ## B ## which is the characteristic magnetization curve for a typical ferromagnetic material.

Conclusion:

The reader should now have a better understanding of the role of the magnetic surface currents in maintaining the magnetization in a permanent magnet and in generating the magnetic fields both inside and outside the permanent magnet.

B.S. Physics with High Departmental Distinction= University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1977. M.S. Physics UCLA 1979. Worked for 25+ years as a physicist doing electro-optic research at Northrop-Grumman in Rolling Meadows, Illinois.

I'm just now adding this thread to the discussion for the sake of completeness, and see particularly post 73 by @vanhees71 , but even a good portion of the thread, where the merits and lack of merit of the magnetic surface current model are discussed in much detail, as well as the complete thread, where other details about magnetostatic and electromagnetic concepts are discussed :

https://www.physicsforums.com/threa…electric-induction.962632/page-4#post-6110191

It might be useful for those interested in the subject of permanent magnets and magnetic surface currents to look through this thread, and, in particular, posts 18 and 19 of this thread, for some additional detail on the subject: https://www.physicsforums.com/threa…-function-of-temperature.950326/#post-6020315

I'd say, it's just a mathematical identity. Instead of the magnetization of the permanent magnet you can as well with the magnetization-current density,

$$vec{j}_{text{mag}}=2c vec{nabla} times vec{M},$$

where ##vec{M}## is the magnetization density of the material.

In classical electrodynamics, I don't see how to make a difference between magnetization and this current density. Of course, physically ferromagnetism is not due to currents but due to the spin orientations (meaning also an orientation of their elementary magnetic moments) of electrons. From the very wording of this sentence it becomes clear that ferromagnetism cannot be understood microscopically within classical electrodynamics, but you need quantum theory. You also need the fermionic nature of the electrons and the related phenomenon of "exchange forces" (which of course is a somewhat unfortunate name, but that's what's stuck in the slang of quantum physicists). An interesting paper on the state of affairs of ferromagnetism was published around 2011. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1106.3795.pdf It's interesting that someone (Dr. Yuri Mnyukh) who performed numerous experiments on ferromagnetic properties including on the ferromagnetic to paramagnetic transition at the Curie temperature in various materials seemed rather dissatisfied with what was the present understanding of ferromagnetism at that time.

I'd say, it's just a mathematical identity. Instead of the magnetization of the permanent magnet you can as well with the magnetization-current density,

$$vec{j}_{text{mag}}=2c vec{nabla} times vec{M},$$

where ##vec{M}## is the magnetization density of the material.

In classical electrodynamics, I don't see how to make a difference between magnetization and this current density. Of course, physically ferromagnetism is not due to currents but due to the spin orientations (meaning also an orientation of their elementary magnetic moments) of electrons. From the very wording of this sentence it becomes clear that ferromagnetism cannot be understood microscopically within classical electrodynamics, but you need quantum theory. You also need the fermionic nature of the electrons and the related phenomenon of "exchange forces" (which of course is a somewhat unfortunate name, but that's what's stuck in the slang of quantum physicists).

I would like to post one additional comment about how the above model with the equation ## M=chi' B ## is very much an oversimplification of things. This paper was a result of this author's attempts to tie together the "pole model" of magnetism with the "surface current" model. That part was mathematically 100% successful, and showed the two give identical results, with the surface current model providing a more sound explanation for the magnetic fields ## B ## that are generated by a magnetization ## M ##. The assumption of a functional dependence of ## M=M(B) ## is much better at explaining some of the aspects of the permanent magnet than any equation of the form ## M=M(H) ##. This "functional" dependence ## M=M(B) ## is very much unexact though because of the exchange effect. What the magnetization ## M ## decides to do at position ## vec{r} ## is far too dependent on the magnetization at ## vec{r}+Delta vec{r} ## to be able to assume that ## M ## at position ## vec{r} ## is responding only to ## B ## at ## vec{r} ## and nothing else. Any mathematical treatment of this is, however, well beyond the scope of this paper. A quantum mechanical formalism that takes this into account might also be able to explain why some materials make permanent magnets, while others have their magnetization ## M ## return to near zero upon removal of the applied field ## H ##. ## \ ## One additional comment: A Weiss Mean Field Model that uses ## B ## as the applied field (where ## B ## includes the fields from the surface currents) rather than simply just ## H ## would be an improvement to the Mean Field discussion found in Reif's Statistical and Thermal Physics textbook.

I would like to post a "link" to a recent thread that gives some additional insight into magnetism phenomena. It is an experiment that involves the Curie temperature, and they really have an interesting experiment. In addition, you might even find of interest the additional experiment that I did with a boy scout compass and a cylindrical magnet that is mentioned near the end of the thread. (see post #21 ) https://www.physicsforums.com/threa…perature-relationship-in-ferromagnets.923380/

If we want to discuss the magnetic properties of the material, we must, first of all, to know what it is and how magnetism arises.

Science has not given true evidence of the cause of magnetism in the universe, nor in the matter.

To all this can be understood, I will try to give you the basic guidelines to understand this enigma.

1. -magnetizam the residual out of balance condition between ether from which it is formed and the substance gluons incurred pair annihilation of a positron-electron. Proof: Each chemical element that has more protons of neutrons, it may causes a magnetization in 3kg as the particle (and 3kvarka gluons 3), can find another gluon. If the gluon enters 3kg particle, resulting neutron.

Now we need to know how to form a permanent magnet in nature and how it can affect the other materials that causes them to electricity.

If this detail is understood, we can get an infinite amount of electricity in a very free way.

But the problem is how to convince the unconscious institutions and science to understand the structure of the universe. Maybe it's not the right time, but we have a strong resistance and the institutions of science and with the state authorities (the fault is tajkunizam).

ZapperZ:

Hi, You asked, “But is there really a surface current that is responsible for the magnetic field of a ferromagnet? Or is this simply a model that is made to match the magnetic field geometry?”

If you look at figure 30 here http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/302l/lectures/node77.html

it may help you to make up your mind.

Charles, if we have a little hollow chamber at the middle of a huge permanent magnet, what would a compass inside this chamber behave like?

Without the surface currents, magnetized materials would produce rather small magnetic fields, and in addition, there wouldn't be a significant magnetic field inside the material to maintain the magnetization. (The exchange interaction, which is energetically much stronger, would still dominate, but by itself, would not explain why it takes such a tremendously strong solenoid current in the reverse direction to reverse the direction of magnetization in a permanent magnet. This feature is explained simply by the surface currents.) ## \ ## [USER=6230]@ZapperZ[/USER] Your suggestion for an alternate title, to change the word from "explained" to "described" is a good one. ## \ ## The type of discussion I'm still hoping for though is a comparison of the calculations of magnetic "pole" model with those of the "surface current." Even J.D. Jackson's Classical Electrodynamics textbook, which emphasizes the "pole" model, treats ## H ##, (including the ## H ## from the "poles"), erroneously as a second type of magnetic field (besides what he calls the magnetic induction ## B ##). A thorough study of the surface current calculations showed that the ## H ## from the poles in the material is simply a geometric correction factor for geometries other than the cylinder of infinite length. The article is intended to help give the student a solid introduction to some E&M fundamentals, rather than trying to explain any details of the exchange interaction.

[QUOTE="Dale, post: 5682019, member: 43978"]I think you are talking about Maxwell's equations vs QED.I am talking about Maxwell's equations formulated in terms of magnetization or in terms of bound currents. Maxwell's equations do not explain magnetization either way, it is phenomenological either way.”I don't know why this is rather difficult to understand. Maybe I'll try it this way:Quantum magnetism explains why such-and-such a material is a ferromagnet. Once it has become a ferromagnet, it then produces a magnetic field. This magnetic field can then be modeled as being produced by some "surface currents".Do we have a problem with the statements I made above?If yes, what is the problem?If no, then surface currents cannot explain the existence of a permanent magnet/ferromagnet. It can describe the FIELD generated by the magnet, but not how it became a ferromagnet.If the title of this Insight article reads "Magnetic Fields of Permanent Magnets Described by Magnetic Surface Currents", I would have zero issues with it.Zz.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5682001, member: 6230"]No, they are not equivalent.”I think you are talking about Maxwell's equations vs QED. I am talking about Maxwell's equations formulated in terms of magnetization or in terms of bound currents. Maxwell's equations do not explain magnetization either way, it is phenomenological either way.

[QUOTE="Dale, post: 5681996, member: 43978"]Yes. It is phenomenological. It doesn't matter whether you describe the phenomenon as magnetization or as bound currents. It is just two different equivalent phenomenological descriptions. Sometimes one or the other approach will simplify a specific problem, but other than that they fundamentally share the same limitations.”No, they are not equivalent. One simply describes the magnetic field generated. The other explains why a material becomes a ferromagnet, paramagnet, antiferromagnet, etc.Zz.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5681984, member: 6230"]And this, to me, is the SOURCE of the confusion, and the reason why I objected to the article. Not only did it not explain everything about ferromagnetism, I also claim that it explains nothing about ferromagnetism. It describes the FIELD generated by a ferromagnet, but it says nothing about ferromagnetism.Ferromagnetism is the material, the formation of magnetic ordering within the material. The result of such ordering is the magnetic field. The title of the article is severely misleading when you claim "Permanent Magnets Explained by Magnetic Surface Currents". This was my objection from the very beginning – the use of that language! Claiming that "permanent magnets explained by magnetic surface currents" means that the origin of this permanent magnet is this surface currents. Even you have admitted that this isn't true, but yet, the misleading title, and the first sentence in the article made it sound as if this IS the "explanation" for a ferromagnet.It isn't. It is a way to "explain" the FIELD generated by the ferromagnet. It doesn't explain how ferromagnetism happens. You may think this is a trivial and subtle point, but it isn't, as can already be seen by the misunderstanding made by previous "lay-man" post. If this was an internal note among physicists, I wouldn't have wasted my time because we all know the full story. But this is meant for students and also people who do not have enough understanding of physics to be aware of such things as quantum magnetism. They will walk away thinking that a permanent magnet becomes one due to all these surface currents. That is wagging the dog!Zz.”The students need to start somewhere to learn the material If they learned the part of it presented in the article, I think more of them would be prepared to study the finer details of things like the exchange effect. There was no attempt here to create any kind of sensationalism. It was actually suggested by Greg B. that I change my original title (which was very undramatic), because it didn't do much to attract the reader's attention.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5681940, member: 6230"]This model does not explain the origin of ferromagnetism. It can't. It is fundamentally a phenomenological model.”Yes. It is phenomenological. It doesn't matter whether you describe the phenomenon as magnetization or as bound currents. It is just two different equivalent phenomenological descriptions. Sometimes one or the other approach will simplify a specific problem, but other than that they fundamentally share the same limitations.

[QUOTE="Charles Link, post: 5681958, member: 583509"]The article was not intended to explain everything about ferromagnetism. “And this, to me, is the SOURCE of the confusion, and the reason why I objected to the article. Not only did it not explain everything about ferromagnetism, I also claim that it explains nothing about ferromagnetism. It describes the FIELD generated by a ferromagnet, but it says nothing about ferromagnetism.Ferromagnetism is the material, the formation of magnetic ordering within the material. The result of such ordering is the magnetic field. The title of the article is severely misleading when you claim "Permanent Magnets Explained by Magnetic Surface Currents". This was my objection from the very beginning – the use of that language! Claiming that "permanent magnets explained by magnetic surface currents" means that the origin of this permanent magnet is this surface currents. Even you have admitted that this isn't true, but yet, the misleading title, and the first sentence in the article made it sound as if this IS the "explanation" for a ferromagnet.It isn't. It is a way to "explain" the FIELD generated by the ferromagnet. It doesn't explain how ferromagnetism happens. You may think this is a trivial and subtle point, but it isn't, as can already be seen by the misunderstanding made by previous "lay-man" post. If this was an internal note among physicists, I wouldn't have wasted my time because we all know the full story. But this is meant for students and also people who do not have enough understanding of physics to be aware of such things as quantum magnetism. They will walk away thinking that a permanent magnet becomes one due to all these surface currents. That is wagging the dog!Zz.

The article was not intended to explain everything about ferromagnetism. A very important part of the ferromagnetism is the exchange interaction which couples adjacent spins to each other (to have it be very energetically favorable for them to be co-aligned.) The exchange interaction also is what makes ferromagnetism exist to very high temperatures (the Curie temperature), rather than occurring at only very low temperatures (as would be the case without the exchange interaction.) In any case, I think most physics students should find it worthwhile reading, and it is a topic that seems to have become deemphasized in the curriculum because there are so many other things to learn. It certainly should be an improvement over the magnetic "pole" model that is taught in many of the older E&M textbooks. ## \ ## As stated previously in the discussions above, I have done lengthy calculations that show the precise equivalence of the magnetic field ## B ## computed from the "pole" model and "surface current" model in all cases. If the student has extra time, I would even recommend they study the magnetic "pole" model as well, because it is mathematically simpler and also very useful for computations of the resulting magnetization and magnetic field using Legendre polynomial methods, such as a sphere of magnetic material in a uniform magnetic field.

[QUOTE="Raxxer, post: 5681932, member: 605516"]This works well to explain the details to the lay-man, though I will admit that it seems logical that a permanent magnet could exist because of the positions of electrons in said ferromagnetic materials and their symmetries.”Unfortunately, this is the exact reason why I had problems with this model. While you may use it to arrive at the magnetic field that a particular geometry of permanent magnet can generate, your conclusion that this somehow explains how "… a permanent magnet could exist because of the positions of electrons in said ferromagnetic materials and their symmetries…." is not correct. This model does not explain the origin of ferromagnetism. It can't. It is fundamentally a phenomenological model.Zz.

This works well to explain the details to the lay-man, though I will admit that it seems logical that a permanent magnet could exist because of the positions of electrons in said ferromagnetic materials and their symmetries.

Additional comment on this subject: I am hoping some of the readers take the time to calculate and compare the results from the magnetic "pole" model with those from the magnetic "surface current" model. (e.g. for the cylindrical and spherical geometries for uniform magnetization.) The universities don't seem to be emphasizing this material very much these days in the curriculum because there is so much other material to learn, but I think the reader may find it quite interesting that these two very different methods give identical answers for the magnetic field ## B ## both inside and outside of the material.

[QUOTE="fluidistic, post: 5668737, member: 122352"]Note that there's an ongoing discussion of this in reddit : https://www.reddit.com/r/Physics/comments/5obsn0/permanent_magnets_explained_by_magnetic_surface/.”From what I can see of the "reddit" comments, they are a couple of levels below the level of physics that is done at Physics Forums. At Physics Forums, the other members don't always agree with you, but they normally put some careful thought and effort into their ideas and opinions. :) :) :)

It might be worth mentioning that there are basically two ways to compute the magnetic fields of magnetic materials: The "pole method" and the magnetic surface current method. ## \ ## One advantage of the "pole " method is that the mathematics are a little simpler, and for a simple uniformly magnetized bar magnet, all that is needed to compute the magnetic field is to assign a "+" pole to one endface, and a "-" pole to the other, and the magnetic field ## H ## from each outside the magnetic obeys the inverse square law. The poles have magnetic surface charge density equal to ## sigma_m=M cdot hat{n} ##. Inside the magnet, the ## H ## points opposite from the ## M ##, and the magnetic field ## B=H+4 pi M ## will be found to point in the same direction as the magnetization ## M ##. A second advantage of the "pole" method is that the Legendre polynomial method can be employed for what would otherwise be very difficult calculations.## \ ## The magnetic surface current method doesn't recognize the existence of any magnetic poles, but instead has a magnetic surface current per unit length ## K_m=c M times hat{n} ## on the outer surface of the cylindrical magnet, and the magnetic field ## B ## is computed everywhere by using Biot-Savart's law. The Biot-Savart integrals used to compute the magnetic field ## B ## are much more complex, and it is rather remarkable that these integrals get the exact same answer for the magnetic field ## B ## as the simpler "pole" method in all cases. Meanwhile, the magnetic fields are explained in this method as arising from currents=in this case "bound" currents. The agreement between the two methods in the computed magnetic field ## B ## is quite remarkable, and the surface current method offers the advantage of explaining the underlying physics=i.e. magnetic fields arise from electrical currents. It is for these reasons that this author finds the magnetic surface current method of calculating magnetic fields in the materials as one that would be quite useful to be emphasized in the physics undergraduate curriculum. ## \ ##[USER=43978]@Dale[/USER] and [USER=260864]@vanhees71[/USER] I would enjoy any feedback you might have.

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5668622, member: 260864"]I like the mathematics displayed in this Insights article very much. However one should indeed emphasize that the surface currents are mathematical equivalents to mimic the influence of magnetization of the material in terms of the usual local Maxwell equations, as stressed by [USER=6230]@ZapperZ[/USER].”The magnetic surface currents are what results from Maxwell's equations, but the result is that the magnetic field that occurs in most magnetic solids is basically from non-local causes. If you look at the equation ## B=H+4 pi M ## as presented by the pole method where ## H ## includes contributions from the poles (the long cylinder geometry essentially has no poles), you could easily conclude that the magnetic field ## B ## is caused by a local magnetization ## M ##. Calculations with the magnetic surface currents shows that the magnetic field is instead caused by the non-local surface currents. ## \ ## For a thin disc shape, the surface currents are minimal and the magnetic field from such a shape is predicted to be rather weak. At least in one set of flat "refrigerator sticker" type magnets that I have, I found by experiment that they actually contain thin rows, spaced about 1/8" apart of alternating + and – magnetization.

Note that there’s an ongoing discussion of this in reddit : https://www.reddit.com/r/Physics/comments/5obsn0/permanent_magnets_explained_by_magnetic_surface/.

I like the mathematics displayed in this Insights article very much. However one should indeed emphasize that the surface currents are mathematical equivalents to mimic the influence of magnetization of the material in terms of the usual local Maxwell equations, as stressed by @ZapperZ.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5668189, member: 6230"]But is there really a surface current that is responsible for the magnetic field of a ferromagnet? Or is this simply a model that is made to match the magnetic field geometry?”In general the goal of science is to provide models that work, and asking "is there really …" is just a philosophical exercise. If your phisophocal preference is to treat it as just a model and not real then that is fine, it is your choice. You are free to think of it merely as a computational aid and others are free to consider it to be real. [QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5668215, member: 6230"]if there's a surface current, then there should be a surface resistance”The J in Ohm's law is the free current. The bound current idea doesn't predict a surface resistance, so its absence isn't contradictory evidence.

[USER=20524]@jtbell[/USER] Might we have your inputs on the topic? In some previous discussions of magnetic surface currents (about a year ago), you were very much a proponent of the concept, where you described in detail the form of the derivation that Griffiths uses in his text.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5668226, member: 6230"]And this is what I meant as it being simply a MODELED current. Haven't I said that there really isn't an actual, real surface current?I can solve an electrostatic problem of a charge above a conductor plane by using an image charge. Everything about it is accurate. But is there really an image charge? No, there isn't! It is there simply to MODEL the charge distribution on the surface of the conductor. This charge distribution is real. The image charge isn't.Your surface current can be used to model the magnetic field produced by the magnet. This is NOT is dispute. However, this surface current isn't real, similar to the image charge. It doesn't explain the origin of ferromagnetism. That is my point of contention in your article.Zz.”I didn't include the exchange effect, because that is an additional topic that is very necessary to explain the high Curie temperatures, but isn't needed to explain the magnetic fields that are produced by permanent magnets. To first order, the exchange effect causes a coupling of adjacent spins to create clusters of spins (perhaps 100 or more) that all respond as a unit. Thereby, the ## mu_s cdot B/kT ## that defines the Curie temperature will have a ## mu_s ## that is much more than a single electron spin.

[QUOTE="Charles Link, post: 5668219, member: 583509"]The origin of these magnetic surface currents is the magnetic moment at the atomic level. These states will persist without experiencing any ohmic losses. This is even the case with the plastic lamination that is used to block the Faraday currents in the ac transformer. The plastic laminations do not block the magnetic surface currents, because there is no actual electrical charge transport. The magnetic field occurs in the transformer from the surface currents, and meanwhile the "eddy" currents are successfully blocked.”And this is what I meant as it being simply a MODELED current. Haven't I said that there really isn't an actual, real surface current?I can solve an electrostatic problem of a charge above a conductor plane by using an image charge. Everything about it is accurate. But is there really an image charge? No, there isn't! It is there simply to MODEL the charge distribution on the surface of the conductor. This charge distribution is real. The image charge isn't.Your surface current can be used to model the magnetic field produced by the magnet. This is NOT is dispute. However, this surface current isn't real, similar to the image charge. It doesn't explain the origin of ferromagnetism. That is my point of contention in your article.Zz.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5668215, member: 6230"]And I want others to think "Wait, if there's a surface current, then there should be a surface resistance (permanent magnets are not superconductors), and since there's no net potential to maintain this current, this current will decay and die off very quickly. And that means that if the origin of this magnetic field is this surface current, then the magnetic field of a permanent magnet should die off in seconds!Zz.”The origin of these magnetic surface currents is the magnetic moment at the atomic level. These states will persist without experiencing any ohmic losses. This is even the case with the plastic lamination that is used to block the Faraday currents in the ac transformer. The plastic laminations do not block the magnetic surface currents, because there is no actual electrical charge transport. The magnetic field occurs in the transformer from the surface currents, and meanwhile the "eddy" currents are successfully blocked.

[QUOTE="Charles Link, post: 5668208, member: 583509"]I've given as much rebuttal as I can for the moment. All I can do is ask for others to carefully look over the calculations and provide their opinions.”And I want others to think "Wait, if there's a surface current, then there should be a surface resistance (permanent magnets are not superconductors), and since there's no net potential to maintain this current, this current will decay and die off very quickly. And that means that if the origin of this magnetic field is this surface current, then the magnetic field of a permanent magnet should die off in seconds!Zz.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5668206, member: 6230"]You don't seem to understand the problem.There's nothing wrong with the calculation. If you want to model the magnetic field as being generated by a current, then fine! This was never in dispute!But there is an implicit idea that this surface current is REAL for a permanent magnet. I question this, and I've asked for evidence to support that argument, rather than simply regurgitating the model. An electron has a magnetic moment. It has no "surface current". The requirement for the existence of a current to always produce a magnetic field is not valid.Zz.”I've given as much rebuttal as I can for the moment. All I can do is ask for others to carefully look over the calculations and provide their opinions.

[QUOTE="Charles Link, post: 5668203, member: 583509"]I have already gotten feedback from a well-established E&M professor at the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana. Please don't be too quick to discard the calculations.”You don't seem to understand the problem.There's nothing wrong with the calculation. If you want to model the magnetic field as being generated by a current, then fine! This was never in dispute!But there is an implicit idea that this surface current is REAL for a permanent magnet. I question this, and I've asked for evidence to support that argument, rather than simply regurgitating the model. An electron has a magnetic moment. It has no "surface current". The requirement for the existence of a current as a requirement to produce a magnetic field is not valid.Zz.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5668198, member: 6230"]I have done something similar. This is an exercise the same way I ask my students to compute the centripetal force that is required to keep an electron in "orbit" around a nucleus. But none of this has any bearing on reality.You could have easily showed me an experiment that actually measured this surface current, and I'll be satisfied with that. But my claim here is that this is nothing more than a model-equivalent, that IF this was modeled by currents, then it will have such-and-such a configuration and value. The magnetic field of permanent magnets is not caused by surface currents.Zz.”I have already gotten feedback from a well-established E&M professor at the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana. Please don't be too quick to discard the calculations.

[QUOTE="Charles Link, post: 5668194, member: 583509"]I urge you to read through the derivation that Griffiths does for the magnetic potential ## A ##. He begins with the potential for a single magnetic dipole and then computes the potential ## A ## for an arbitrary distribution of magnetic dipoles. It is a rather unique and roundabout proof that gets the result that the potential ## A ## consists of two terms: Magnetic currents from ## nabla times M=J_m/c ## and magnetic surface currents ## K_m=c M times hat{n} ##. He does it using SI units, and doesn't really emphasize the very important result.”I have done something similar. This is an exercise the same way I ask my students to compute the centripetal force that is required to keep an electron in "orbit" around a nucleus. But none of this has any bearing on reality.You could have easily showed me an experiment that actually measured this surface current, and I'll be satisfied with that. But my claim here is that this is nothing more than a model-equivalent, that IF this was modeled by currents, then it will have such-and-such a configuration and value. The magnetic field of permanent magnets is not caused by surface currents.Zz.

[QUOTE="ZapperZ, post: 5668189, member: 6230"]There is something not quite right with this.Let's say that I measure some magnetic field geometry. Without knowing the source, and simply looking at the geometry and the boundary conditions, I can come up with a particular geometry of the current source. This is what the article is doing, i.e. deducing the current source based on the fact that there is some configuration of a magnetic field.But is there really a surface current that is responsible for the magnetic field of a ferromagnet? Or is this simply a model that is made to match the magnetic field geometry?When I move a magnet into a coil, I get create a magnetic field that opposes the change in the magnetic field experienced by the coil. This opposing magnetic field induces a current in the coil. This is not a "model" current. It is real. If you connect a bulb to the circuit, it'll light up.So is this surface current real, or is it simply a model that matches the field geometry? If I connect 2 ends a wire to various parts of the surface of the magnet, will I measure a current?The picture of small, closed current loops to model atomic magnetic moment is highly outdated and not very accurate. Maybe to the first approximation, it might be useful, but that is as far as it can go. There are no current loops, and as far as I know, there are no ferromagnetic surface currents. There are modeled Amperian currents to emulate the magnetic field produced by the magnet, but this isn't real.The other problem with this scenario is the difference between ferromagnets and paramagnets. If all we care about is this surface currrents, then why, in some material, the magnetization dies off when the external field goes away, while in permanent magnets, they stay aligned. This is one of the topics in quantum magnetism, where, among others, the Heisenberg coupling between nearest neighbor, next-nearest neighbor, next-next-nearest neighbor, etc… magnetic moments comes into play. The determination of the magnetic moment configuration of the lowest energy state is significant to result whether something is a paramagnet, ferromagnet, antiferromagnet, etc. This is the ORIGIN of permanent magnet, not the existence of "surface currents".Zz.”I urge you to read through the derivation that Griffiths does for the magnetic potential ## A ##. He begins with the potential for a single magnetic dipole and then computes the potential ## A ## for an arbitrary distribution of magnetic dipoles. It is a rather unique and roundabout proof that gets the result that the potential ## A ## consists of two terms: Magnetic currents from ## nabla times M=J_m/c ## and magnetic surface currents ## K_m=c M times hat{n} ##. He does it using SI units, and doesn't really emphasize the very important result.

There is something not quite right with this.Let's say that I measure some magnetic field geometry. Without knowing the source, and simply looking at the geometry and the boundary conditions, I can come up with a particular geometry of the current source. This is what the article is doing, i.e. deducing the current source based on the fact that there is some configuration of a magnetic field.But is there really a surface current that is responsible for the magnetic field of a ferromagnet? Or is this simply a model that is made to match the magnetic field geometry?When I move a magnet into a coil, I get create a magnetic field that opposes the change in the magnetic field experienced by the coil. This opposing magnetic field induces a current in the coil. This is not a "model" current. It is real. If you connect a bulb to the circuit, it'll light up.So is this surface current real, or is it simply a model that matches the field geometry? If I connect 2 ends a wire to various parts of the surface of the magnet, will I measure a current?The picture of small, closed current loops to model atomic magnetic moment is highly outdated and not very accurate. Maybe to the first approximation, it might be useful, but that is as far as it can go. There are no current loops, and as far as I know, there are no ferromagnetic surface currents. There are modeled Amperian currents to emulate the magnetic field produced by the magnet, but this isn't real.The other problem with this scenario is the difference between ferromagnets and paramagnets. If all we care about is this surface currrents, then why, in some material, the magnetization dies off when the external field goes away, while in permanent magnets, they stay aligned. This is one of the topics in quantum magnetism, where, among others, the Heisenberg coupling between nearest neighbor, next-nearest neighbor, next-next-nearest neighbor, etc… magnetic moments comes into play. The determination of the magnetic moment configuration of the lowest energy state is significant to result whether something is a paramagnet, ferromagnet, antiferromagnet, etc. This is the ORIGIN of permanent magnet, not the existence of "surface currents".Zz.

The explanation given of magnetic surface currents for computing the magnetic fields is also mathematically in complete agreement with the "pole method" that many of the older generation use to compute the magnetic field. This author has done calculations to show the mathematical equivalence of the two methods. The magnetic surface current method provides a much better understanding of the underlying physics while the "pole method", although getting the precisely correct answer for the magnetic field ## B ##, can easily give incorrect interpretations to what the ## H ## from the poles represents, particularly in the material. For a more complete discussion of the pole method, I refer the reader to some calculations that I did connecting the pole method to the magnetic surface current method: https://www.overleaf.com/read/kdhnbkpypxfk This "Overleaf" paper was my very first attempt at Latex, so that some of the typing may appear a little clumsy, but hopefully you find it readable.

Hard work paid off, nice second Insight Charles!