Struggles With the Continuum: Point Particles and the Electromagnetic Field

In these posts, we’re seeing how our favorite theories of physics deal with the idea that space and time are a continuum, with points described as lists of real numbers. We’re not asking if this idea is true: there’s no clinching evidence to answer that question, so it’s too easy to let one’s philosophical prejudices choose the answer. Instead, we’re looking to see what problems this idea causes, and how physicists have struggled to solve them.

We started with the Newtonian mechanics of point particles attracting each other with an inverse square force law. We found strange ‘runaway solutions’ where particles shoot to infinity in a finite amount of time by converting an infinite amount of potential energy into kinetic energy.

Then we added quantum mechanics, and we saw this problem went away, thanks to the uncertainty principle.

Now let’s take away quantum mechanics and add special relativity. Now our particles can’t go faster than light. Does this help?

Table of Contents

Point particles interacting with the electromagnetic field

Special relativity prohibits instantaneous action at a distance. Thus, most physicists believe that special relativity requires that forces be carried by fields, with disturbances in these fields propagating no faster than the speed of light. The argument for this is not watertight, but we seem to actually see charged particles transmitting forces via a field, the electromagnetic field — that is, light. So, most work on relativistic interactions brings in fields.

Classically, charged point particles interacting with the electromagnetic field are described by two sets of equations: Maxwell’s equations and the Lorentz force law. The first are a set of differential equations involving:

• the electric field ##\vec E## and magnetic field ##\vec B##, which in special relativity are bundled together into the electromagnetic field ##F##, and

• the electric charge density ##\rho## and current density ##\vec \jmath##, which are bundled into another field called the ‘four-current’ ##J##.

By themselves, these equations are not enough to completely determine the future given initial conditions. In fact, you can choose ##\rho## and ##\vec \jmath## freely, subject to the conservation law

$$ \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot \vec \jmath = 0. $$

For any such choice, there exists a solution of Maxwell’s equations for ##t \ge 0## given initial values for ##\vec E## and ##\vec B## that obey these equations at ##t = 0##.

Thus, to determine the future given initial conditions, we also need equations that say what ##\rho## and ##\vec{\jmath}## will do. For a collection of charged point particles, they are determined by the curves in spacetime traced out by these particles. The Lorentz force law says that the force on a particle of charge ##e## is

$$ \vec{F} = e (\vec{E} + \vec{v} \times \vec{B}) $$

where ##\vec v## is the particle’s velocity and ##\vec{E}## and ##\vec{B}## are evaluated at the particle’s location. From this law we can compute the particle’s acceleration if we know its mass.

The trouble starts when we try to combine Maxwell’s equations and the Lorentz force law in a consistent way, with the goal being to predict the future behavior of the ##\vec{E}## and ##\vec{B}## fields, together with particles’ positions and velocities, given all these quantities at ##t = 0##. Attempts to do this began in the late 1800s. The drama continues today, with no definitive resolution! You can find good accounts, available free online, by Feynman and by Janssen and Mecklenburg. Here we can only skim the surface.

The first sign of a difficulty is this: the charge density and current associated to a charged particle are singular, vanishing off the curve it traces out in spacetime but ‘infinite’ on this curve. For example, a charged particle at rest at the origin has

$$ \rho(t,\vec x) = e \delta(\vec{x}), \qquad \vec{\jmath}(t,\vec{x}) = \vec{0} $$

where ##\delta## is the Dirac delta and ##e## is the particle’s charge. This in turn forces the electric field to be singular at the origin. The simplest solution of Maxwell’s equations consisent with this choice of ##\rho## and ##\vec\jmath## is

$$ \vec{E}(t,\vec x) = \frac{e \hat{r}}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 r^2}, \qquad \vec{B}(t,\vec x) = 0 $$

where ##\hat{r}## is a unit vector pointing away from the origin and ##\epsilon_0## is a constant called the permittivity of free space.

In short, the electric field is ‘infinite’, or undefined, at the particle’s location. So, it is unclear how to define the ‘self-force’ exerted by the particle’s own electric field on itself. The formula for the electric field produced by a static point charge is really just our old friend, the inverse square law. Since we had previously ignored the force of a particle on itself, we might try to continue this tactic now. However, other problems intrude.

In relativistic electrodynamics, the electric field has energy density equal to

$$ \frac{\epsilon_0}{2} |\vec{E}|^2 . $$

Thus, the total energy of the electric field of a point charge at rest is proportional to

$$ \displaystyle{ \frac{\epsilon_0}{2} \int_{\mathbb{R}^3} |\vec{E}|^2 \, d^3 x =

\frac{e^2}{8 \pi \epsilon_0} \int_0^\infty \frac{1}{r^4} \, r^2 dr. } $$

But this integral diverges near ##r = 0##, so the electric field of a charged particle has an infinite energy!

How, if at all, does this cause trouble when we try to unify Maxwell’s equations and the Lorentz force law? It helps to step back in history. In 1902, the physicist Max Abraham assumed that instead of a point, an electron is a sphere of radius ##R## with charge evenly distributed on its surface. Then the energy of its electric field becomes finite, namely:

$$ E = \frac{e^2}{8 \pi \epsilon_0} \int_{R}^\infty \frac{1}{r^4} \, r^2 dr = \frac{1}{2} \frac{e^2}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 R} $$

where ##e## is the electron’s charge.

Abraham also computed the extra momentum a moving electron of this sort acquires due to its electromagnetic field. He got it wrong because he didn’t understand Lorentz transformations. In 1904 Lorentz did the calculation right. Using the relationship between velocity, momentum, and mass, we can derive from his result a formula for the ‘electromagnetic mass’ of the electron:

$$ m = \frac{2}{3} \frac{e^2}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 R c^2} $$

where ##c## is the speed of light. We can think of this as the extra mass an electron acquires by carrying an electromagnetic field along with it.

Putting the last two equations together, these physicists obtained a remarkable result:

$$ E = \frac{3}{4} mc^2 .$$

Then, in 1905, a fellow named Einstein came along and made it clear that the only reasonable relation between energy and mass is

$$ E = mc^2 .$$

What had gone wrong?

In 1906, Poincaré figured out the problem. It is not a computational mistake, nor a failure to properly take special relativity into account. The problem is that like charges repel, so if the electron were a sphere of charge it would explode without something to hold it together. And that something — whatever it is — might have energy. But their calculation ignored that extra energy.

In short, the picture of the electron as a tiny sphere of charge, with nothing holding it together, is incomplete. And the calculation showing ##E = \frac{3}{4}mc^2##, together with special relativity saying ##E = mc^2##, shows that this incomplete picture is inconsistent. At the time, some physicists hoped that all the mass of the electron could be accounted for by the electromagnetic field. Their hopes were killed by this discrepancy.

Nonetheless it is interesting to take the energy ##E## computed above, set it equal to ##m_e c^2## where ##m_e## is the electron’s observed mass, and solve for the radius ##R##. The answer is

$$ \displaystyle{ R = \frac{1}{8 \pi \epsilon_0} \frac{e^2}{m_e c^2} } \approx 1.4 \times 10^{-15} \mathrm{meters} .$$

In the early 1900s, this would have been a remarkably tiny distance: ##0.00003## times the Bohr radius of a hydrogen atom. By now we know this is roughly the radius of a proton. We know that electrons are not spheres of this size. So at present, it makes more sense to treat the calculations so far as a prelude to some kind of limiting process where we take ##R \to 0##. These calculations teach us two lessons.

First, the electromagnetic field energy approaches ##+\infty## as we let ##R \to 0##, so we will be hard-pressed to take this limit and get a well-behaved physical theory. One approach is to give a charged particle its own ‘bare mass’ ##m_\mathrm{bare}## in addition to the mass ##m_\mathrm{elec}## arising from electromagnetic field energy, in a way that depends on ##R##. Then as we take the ##R \to 0## limit we can let ##m_\mathrm{bare} \to -\infty## in such a way that ##m_\mathrm{bare} + m_\mathrm{elec}## approaches a chosen limit ##m##, the physical mass of the point particle. This is an example of ‘renormalization’.

Second, it is wise to include conservation of energy-momentum as a requirement in addition to Maxwell’s equations and the Lorentz force law. Here is a more sophisticated way to phrase Poincaré’s realization. From the electromagnetic field, one can compute a ‘stress-energy tensor’ ##T##, which describes the flow of energy and momentum through spacetime. If all the energy and momentum of an object comes from its electromagnetic field, you can compute them by integrating ##T## over the hypersurface ##t = 0##. You can prove that the resulting 4-vector transforms correctly under Lorentz transformations if you assume the stress-energy tensor has vanishing divergence: ##\partial^\mu T_{\mu \nu} = 0##. This equation says that energy and momentum are locally conserved. However, this equation fails to hold for a spherical shell of charge with no extra forces holding it together. In the absence of extra forces, it violates the conservation of momentum for a charge to feel an electromagnetic force yet not accelerate.

So far we have only discussed the simplest situation: a single charged particle at rest, or moving at a constant velocity. To go further, we can try to compute the acceleration of a small charged sphere in an arbitrary electromagnetic field. Then, by taking the limit as the radius ##r## of the sphere goes to zero, perhaps we can obtain the law of motion for a charged point particle.

In fact this whole program is fraught with difficulties, but physicists boldly go where mathematicians fear to tread, and in a rough way this program was carried out already by Abraham in 1905. His treatment of special relativistic effects was wrong, but these were easily corrected; the real difficulties lie elsewhere. In 1938 his calculations were carried out much more carefully — though still not rigorously — by Dirac. The resulting law of motion is thus called the ‘Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law’.

There are three key ways in which this law differs from our earlier naive statement of the Lorentz force law:

• We must decompose the electromagnetic field in two parts, the ‘external’ electromagnetic field ##F_\mathrm{ext}## and the field produced by the particle:

$$ F = F_\mathrm{ext} + F_\mathrm{ret} . $$

Here ##F_\mathrm{ext}## is a solution Maxwell equations with ##J = 0##, while ##F_\mathrm{ret}## is computed by convolving the particle’s 4-current ##J## with a function called the ‘retarded Green’s function’. This breaks the time-reversal symmetry of the formalism so far, ensuring that radiation emitted by the particle moves outward as ##t## increases. We then decree that the particle only feels a Lorentz force due to ##F_\mathrm{ext}##, not ##F_\mathrm{ret}##. This avoids the problem that ##F_\mathrm{ret}## becomes infinite along the particle’s path as ##r \to 0##.

• Maxwell’s equations say that an accelerating charged particle emits radiation, which carries energy-momentum. Conservation of energy-momentum implies that there is a compensating force on the charged particle. This is called the ‘radiation reaction’. So, in addition to the Lorentz force, there is a radiation reaction force.

• As we take the limit ##r \to 0##, we must adjust the particle’s bare mass ##m_\mathrm{bare}## in such a way that its physical mass ##m = m_\mathrm{bare} + m_\mathrm{elec}## is held constant. This involves letting ##m_\mathrm{bare} \to -\infty## as ##m_\mathrm{elec} \to +\infty##.

It is easiest to describe the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law using standard relativistic notation. So, we switch to units where ##c## and ##4 \pi \epsilon_0## equal 1, let ##x^\mu## denote the spacetime coordinates of a point particle, and use a dot to denote the derivative with respect to proper time. Then the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law says

$$ m \ddot{x}^\mu = e F_{\mathrm{ext}}^{\mu \nu} \, \dot{x}_\nu \; – \; \frac{2}{3}e^2 \ddot{x}^\alpha \ddot{x}_\alpha \, \dot{x}^\mu \; + \; \frac{2}{3}e^2 \dddot{x}^\mu

.$$

The first term at right is the Lorentz force, which looks more elegant in this new notation. The second term is fairly intuitive: it acts to reduce the particle’s velocity at a rate proportional to its velocity (as one would expect from friction), but also proportional to the squared magnitude of its acceleration. This is the ‘radiation reaction’.

The last term called the ‘Schott term’, is the most shocking. Unlike all familiar laws in classical mechanics, it involves the third derivative of the particle’s position!

This seems to shatter our original hope of predicting the electromagnetic field and the particle’s position and velocity given their initial values. Now it seems we need to specify the particle’s initial position, velocity, and acceleration.

Furthermore, unlike Maxwell’s equations and the original Lorentz force law, the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law is not symmetric under time reversal. If we take a solution and replace ##t## with ##-t##, the result is not a solution. The problem here is the second term, not the third. Like the force of friction, radiation reaction acts to make a particle lose energy as it moves into the future, not the past.

The reason is that our assumptions have explicitly broken time symmetry. The splitting ##F = F_\mathrm{ext} + F_\mathrm{ret}## says that a charged accelerating particle radiates into the future, creating the field ##F_\mathrm{ret}##, and is affected only by the remaining electromagnetic field ##F_\mathrm{ext}##.

Worse, the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law has counterintuitive solutions. Suppose for example that ##F_\mathrm{ext} = 0##. Besides the expected solutions where the particle’s velocity is constant, there are solutions for which the particle accelerates indefinitely, approaching the speed of light! These are called ‘runaway solutions’. In these runaway solutions, the acceleration as measured in the frame of reference of the particle grows exponentially with the passage of proper time.

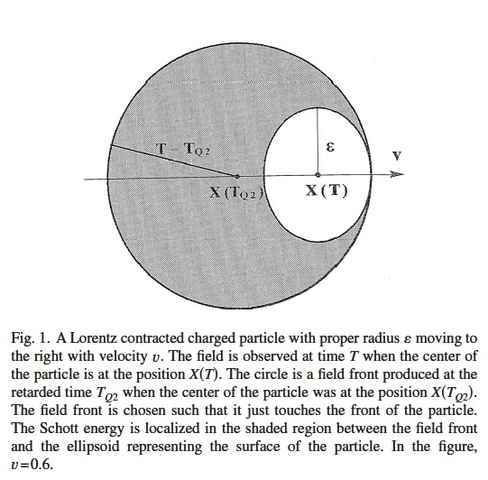

So, the notion that special relativity might help us avoid the pathologies of Newtonian point particles interacting gravitationally — 5-body solutions where particles shoot to infinity in finite time — is cruelly mocked by the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law. Particles cannot move faster than light, but even a single particle can extract an arbitrary amount of energy-momentum from the electromagnetic field in its immediate vicinity and use this to propel itself forward at speeds approaching that of light. The energy stored in the field near the particle is sometimes called ‘Schott energy’.

Thanks to the Schott term in the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law, the Schott energy can be converted into kinetic energy for the particle. The details of how this works are nicely discussed in a paper by Øyvind Grøn, so click the link and read that if you’re interested. I’ll just show you a picture from that paper:

So even one particle can do crazy things! But worse, suppose we generalize the framework to include more than one particle. The arguments for the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law can be generalized to this case. The result is simply that each particle obeys this law with an external field ##F_\mathrm{ext}## that includes the fields produced by all the other particles. But a problem appears when we use this law to compute the motion of two particles of opposite charge. To simplify the calculation, suppose they are located symmetrically with respect to the origin, with equal and opposite velocities and accelerations. Suppose the external field felt by each particle is solely the field created by the other particle. Since the particles have opposite charges, they should attract each other. However, one can prove they will never collide. In fact, if at any time they are moving towards each other, they will later turn around and move away from each other at ever-increasing speed!

This fact was discovered by C. Jayaratnam Eliezer in 1943. It is so counter-intuitive that several proofs were required before physicists believed it.

None of these strange phenomena have ever been seen experimentally. Faced with this problem, physicists have naturally looked for ways out. First, why not simply cross out the ##\dddot{x}^\mu## term in the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force? Unfortunately the resulting simplified equation

$$ m \ddot{x}^\mu = e F_{\mathrm{ext}}^{\mu \nu} \, \dot{x}_\nu – \frac{2}{3}e^2 \ddot{x}^\alpha \ddot{x}_\alpha \, \dot{x}^\mu $$

has only trivial solutions. The reason is that with the particle’s path parametrized by proper time, the vector ##\dot{x}^\mu## has constant length, so the vector ##\ddot{x}^\mu## is orthogonal to ##\dot{x}^\mu## . So is the vector ##F_{\mathrm{ext}}^{\mu \nu} \dot{x}_\nu##, because ##F_{\mathrm{ext}}## is an antisymmetric tensor. So, the last term must be zero, which implies ##\ddot{x} = 0##, which in turn implies that all three terms must vanish.

Another possibility is that some assumption made in deriving the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law is incorrect. Of course, the theory is physically incorrect, in that it ignores quantum mechanics and other things, but that is not the issue. The issue here is one of mathematical physics, of trying to formulate a well-behaved classical theory that describes charged point particles interacting with the electromagnetic field. If we can prove this is impossible, we will have learned something. But perhaps there is a loophole. The original arguments for the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law are by no means mathematically rigorous. They involve a delicate limiting procedure, and approximations that were believed, but not proved, to become perfectly accurate in the ##r \to 0## limit. Could these arguments conceal a mistake?

Calculations involving a spherical shell of charge have been improved by a series of authors, and nicely summarized by Fritz Rohrlich. In all these calculations, nonlinear powers of the acceleration and its time derivatives are neglected, and one hopes this is acceptable in the ##r \to 0## limit.

Dirac, struggling with renormalization in quantum field theory, took a different tack. Instead of considering a sphere of charge, he treated the electron as a point from the very start. However, he studied the flow of energy-momentum across the surface of a tube of radius ##r## centered on the electron’s path. By computing this flow in the limit ##r \to 0##, and using conservation of energy-momentum, he attempted to derive the force on the electron. He did not obtain a unique result, but the simplest choice gives the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac equation. More complicated choices typically involve nonlinear powers of the acceleration and its time derivatives.

Since this work, many authors have tried to simplify Dirac’s rather complicated calculations and clarify his assumptions. This book is a good guide:

• Stephen Parrott, Relativistic Electrodynamics and Differential Geometry, Springer, Berlin, 1987.

But more recently, Jerzy Kijowski and some coauthors have made impressive progress in a series of papers that solve many of the problems we have described.

Kijowski’s key idea is to impose conditions on precisely how the electromagnetic field is allowed to behave near the path traced out by a charged point particle. He breaks the field into a ‘regular’ part and a ‘singular’ part:

$$ F = F_\textrm{reg} + F_\textrm{sing} . $$

Here ##F_\textrm{reg}## is smooth everywhere, while ##F_\textrm{sing} ## is singular near the particle’s path, but only in a carefully prescribed way. Roughly, at each moment, in the particle’s instantaneous rest frame, the singular part of its electric field consists of the familiar part proportional to ##1/r^2##, together with a part proportional to ##1/r^3## which depends on the particle’s acceleration. No other singularities are allowed!

On the one hand, this eliminates the ambiguities mentioned earlier: in the end, there are no ‘nonlinear powers of the acceleration and its time derivatives in Kijowski’s force law. On the other hand, this avoids breaking time-reversal symmetry, as the earlier splitting ##F = F_\textrm{ext} + F_\textrm{ret}## did.

Next, Kijowski defines the energy-momentum of a point particle to be ##m \dot{x}##, where ##m## is its physical mass. He defines the energy-momentum of the electromagnetic field to be just that due to ##F_\textrm{reg}##, not ##F_\textrm{sing}##. This amounts to eliminating the infinite ‘electromagnetic mass’ of the charged particle. He then shows that Maxwell’s equations and conservation of total energy-momentum imply an equation of motion for the particle!

This equation is very simple:

$$ m \ddot{x}^\mu = e F_{\textrm{reg}}^{\mu \nu} \, \dot{x}_\nu. $$

It is just the Lorentz force law! Since the troubling Schott term is gone, this is a second-order differential equation. So we can hope that to predict the future behavior of the electromagnetic field, together with the particle’s position and velocity, given all these quantities at ##t = 0##.

And indeed this is true! In 1998, together with Gittel and Zeidler, Kijowski proved that initial data of this sort, obeying the careful restrictions on allowed singularities of the electromagnetic field, determine a unique solution of Maxwell’s equations and the Lorentz force law, at least for a short amount of time. Even better, all this remains true for any number of particles.

There are some obvious questions to ask about this new approach. In the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force law, the acceleration was an independent variable that needed to be specified at ##t = 0## along with position and momentum. This problem disappears in Kijowski’s approach. But how?

We mentioned that the singular part of the electromagnetic field, ##F_\textrm{sing}##, depends on the particle’s acceleration. But more is true: the particle’s acceleration is completely determined by ##F_\textrm{sing}##. So, the particle’s acceleration is not an independent variable because it is encoded into the electromagnetic field.

Another question is: where did the radiation reaction go? The answer is: we can see it if we go back and decompose the electromagnetic field as ##F_\textrm{ext} + F_\textrm{ret}## as we had before. If we take the law

$$ m \ddot{x}^\mu = e F_{\textrm{reg}}^{\mu \nu} \dot{x}_\nu $$

and rewrite it in terms of ##F_\textrm{ext}##, we recover the original Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac law, including the radiation reaction term and Schott term.

Unfortunately, this means that ‘pathological’ solutions where particles extract arbitrary amounts of energy from the electromagnetic field are still possible. A related problem is that apparently nobody has yet proved solutions exist for all time. Perhaps a singularity worse than the allowed kind could develop in a finite amount of time — for example, when particles collide.

So, classical point particles interacting with the electromagnetic field still present serious challenges to the physicist and mathematician. When you have an infinitely small charged particle right next to its own infinitely strong electromagnetic field, trouble can break out very easily!

Particles without fields

Finally, I should also mention attempts, working within the framework of special relativity, to get rid of fields and have particles interact with each other directly. For example, in 1903 Schwarzschild introduced a framework in which each charged particle exerts an electromagnetic force on each other, with no mention of fields. In this setup, forces are transmitted not instantaneously but at the speed of light: the force on one particle at one spacetime point ##x## depends on the motion of some other particle at spacetime point ##y## only if the vector ##x – y## is lightlike. Later Fokker and Tetrode derived this force law from a principle of least action. In 1949, Feynman and Wheeler checked that this formalism gives results compatible with the usual approach to electromagnetism using fields, except for several points:

• Each particle exerts forces only on other particles, so we avoid the thorny issue of how a point particle responds to the electromagnetic field produced by itself.

• There are no electromagnetic fields not produced by particles: for example, the theory does not describe the motion of a charged particle in an ‘external electromagnetic field’.

• The principle of least action guarantees that ‘if ##A## affects ##B## then ##B## affects ##A##’. So, if a particle at ##x## exerts a force on a particle at a point ##y## in its future lightcone, the particle at ##y## exerts a force on the particle at ##x## in its past lightcone. This raises the issue of ‘reverse causality’, which Feynman and Wheeler address.

Besides the reverse causality issue, perhaps one reason this approach has not been more pursued is that it does not admit a Hamiltonian formulation in terms of particle positions and momenta. Indeed, there are a number of ‘no-go theorems’ for relativistic multiparticle Hamiltonians, saying that these can only describe noninteracting particles. So, most work that takes both quantum mechanics and special relativity into account uses fields.

Indeed, in quantum electrodynamics, even the charged point particles are replaced by fields — namely quantum fields! Next time we’ll see whether that helps.

I’m a mathematical physicist. I work at the math department at U. C. Riverside in California, and also at the Centre for Quantum Technologies in Singapore. I used to do quantum gravity and n-categories, but now I mainly work on network theory and the Azimuth Project, which is a way for scientists, engineers and mathematicians to do something about the global ecological crisis.

“The summary of radiation reaction and point charges is very helpful — I hadn’t heard of a lot of the more recent work.”

Thanks! I learned a lot while writing this article; the new work by Kijowski is very nice, but it takes some work to understand it.

“A question that’s been bothering me for a long time is whether there is any sense in which one can prove that a system of charged particles can’t be stable. This seems to be something that all physicists are convinced must be true, but that nobody knows how to prove, or even how to state rigorously.”

I think it’s possible now to state it rigorously, but nobody has proved it.

“Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem possible even to get started on such a proof, because there just isn’t any satisfactory, canonical, self-consistent theory of interacting point charges.”

You might not consider Kijowski’s theory satisfactory – it has annoying features – but it’s rigorously well-defined, it has a lot of good properties, and I’d say it’s the best theory we have of interacting point charges, so it makes some sense to investigate how it behaves. It might even be the best possible theory of interacting point charges where the fields obey Maxwell equations, energy is locally conserved, and energy is given by a formula that physicists would consider reasonable for electrodynamics.

That’s addressing the even more complicated question of motion in gravitational fields (or relativistically spoken in curved background spacetime) and the associated radiation. Anyway, also these authors come to the conclusion that a single accelerated charge radiates off radiation energy, i.e., that there is a radiation-reaction force on the particle (“self energy”).

I believe the review paper by Eric Poisson is also relevant here:

[URL]http://lanl.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/0306052[/URL]

See also the update

[URL]http://lanl.arxiv.org/abs/1102.0529[/URL]

Ad #12: This is of course true. I don’t think that one has been able to accelerate just one elementary particle and measure whether there is radiation emitted from it or not.

Just want tot say that I’m really enjoying this series! Looking forward for more!

I would add that perhaps the greatest champion of classical field theories (Einstein) would agree with the spirit of the papers Vanhees linked in #4 – that point particles are conceptually at odds with field theories; that ideally, a complete field theory models matter as a field concentration, thus inherently finite size with minimum size related to the nature of the field theory. I find the resolution to the self energy issues in these (linked in #4) papers (‘particles’ must be of finite minimum size, all derived with classical EM) far more satisfactory than adding a notion of point particles that needs additional rules.

Of course, this is aesthetic preference. Experiment is not likely to be relevant because neither classical point particles nor classical small charged bodies exist, and the regimes that might distinguish are going to dominated by QED differences from classical EM.

“I still don’t understand these attempts to modify classical electrodynamics, because despite the words at the end of the paper, it is clearly not true that, e.g., single electrons don’t radiate when accelerated by electromagnetic fields. The accelerator physicists would be very glad, if this was true since then you’d not have a problem with synchrotron radiation.”

Stabler explains this himself in his paper:

[SIZE=4]The predictions (i) – (iii) above are not as dire as they appear at first glance because radiation [/SIZE]

observed in classical electromagnetic phenomena [SIZE=4](ƛ ##gg hbar/mc##) usually arises coherently from a large [/SIZE]

number of equivalent radiators

…

Since few measurements of classical electromagnetic phenomena involve very small numbers of coherently radiating particles, it is possible that the above theory is not contradicted by experimental data. Most important it may not yet have been demonstrated that there is any radiated energy for the case N=1.

Back to your example, in synchrotron charged particles move in so-called bunches, one of which contains billions of charged particles. Many charged particles are thus moving and accelerating similarly – in a highly coherent/correlated way. In such a situation, the energy radiated is practically the same in both theories.

Also as far as I know, Stabler’s doubt in the last sentence above is still valid; there is currently no experimental proof that single isolated electron loses energy when accelerating in external field.

”

I cannot follow the final conclusion of the paper. How can a theory, which contradicts the Klein-Nishina formula of the Compton effect be right, which is a non-radiative process, be considered right?[SIZE=4] Usual classical electrodynamics is not in contradiction with this formula. At least it is compatible with the Thompson cross section in the low-energy limit, i.e., for ##E_{gamma} ll m_{text{electron}} c^2##.[/SIZE]

”

[SIZE=4]That is a good remark. The goal for the new theory is not to reproduce the ideas of the older theory, but to be consistent with experiments and to provide new views on them. The standard calculation of scattering cross-section in EM theory considers one particle in external field, which is not at all how the experiment is done. On the other hand, for many coherently moving particles (which seem to be present in the scattering experiments that measured the cross sections in the past), the Frenkel-Stabler kind of theory gives result close to Thomson’s formula.

“”[/SIZE]”

I still think the most convincing conclusion of the failure of a completely self-consistent classical theory of electromagnetically interacting charged point particles is that the very notion of a point particle in classical electrodynamics is flawed.

”

But the point of both papers and of mine here is precisely that the notion of point particle is not flawed at all, at least not from the point of view of internal consistency of the theory. Experimentally, there may be difficulties but that’s to be expected from any model.

I still don’t understand these attempts to modify classical electrodynamics, because despite the words at the end of the paper, it is clearly not true that, e.g., single electrons don’t radiate when accelerated by electromagnetic fields. The accelerator physicists would be very glad, if this was true since then you’d not have a problem with synchrotron radiation. I cannot follow the final conclusion of the paper. How can a theory, which contradicts the Klein-Nishina formula of the Compton effect be right, which is a non-radiative process, be considered right? Usual classical electrodynamics is not in contradiction with this formula. At least it is compatible with the Thompson cross section in the low-energy limit, i.e., for ##E_{gamma} ll m_{text{electron}} c^2##.

I still think the most convincing conclusion of the failure of a completely self-consistent classical theory of electromagnetically interacting charged point particles is that the very notion of a point particle in classical electrodynamics is flawed.

Even in QED the problem is not really solved, because it’s not known, whether QED does really exist as a non-perturbative QFT. Of course in the sense of perturbation theory the radiation-reaction problem is solved by the usual renormalization procedure to get rid of the UV divergences and soft-photon resummations (or equivalently the use of the correct asymptotic states) to get rid of the infrared and collinear divergences due to the masslessness of the photon.

“john baez submitted a new PF Insights post

[URL=’https://www.physicsforums.com/insights/struggles-continuum-part-3/’]Struggles With the Continuum – Part 3[/URL]

[IMG]https://www.physicsforums.com/insights/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/spacetime3-80×80.png[/IMG]

[URL=’https://www.physicsforums.com/insights/struggles-continuum-part-3/’]Continue reading the Original PF Insights Post.[/URL]”

”

In short, the electric field is ‘infinite’, or undefined, at the particle’s location. So, it is unclear how to define the ‘self-force’ exerted by the particle’s own electric field on itself.

”

Indeed! It also means the Poynting theorem is invalid at the points where the particles are (it still holds in between them).

This makes its interpretation as a work-energy theorem invalid. It is thus impossible to infer anything about energy from the Poynting theorem.

”

In relativistic electrodynamics, the electric field has energy density equal to ##[SIZE=4]frac{epsilon_0}{2}|E|^2##.[/SIZE]

”

That is true, but only for regular source distributions, i.e. in macroscopic theory. For point particles, there is no reason to think EM energy is given by this formula. If we use it anyway, we can get anything. The examples you gave and other well-known problems are a result of ignoring this basic problem.

Theory of point particles is not necessarily limit of theory of regular continuous charge distributions (ironically the latter is even more difficult than the former). Point particles have consistent relativistic theory free of the above-mentioned ‘self-force’ and the original Poynting theorem does not play any role, as it is not valid where the particles are. There is a different theorem of similar significance, which however expresses energy as multi-linear function of individual fields of particles, instead of quadratic function of one field.

Cf.

J. Frenkel, Zur Elektrodynamik punktfoermiger Elektronen, Zeits. f. Phys., 32, (1925), p. 518-534. (in German, the first paper I know that gives consistent theory of point particles)

[URL]http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01331692[/URL]

R. C. Stabler, A Possible Modification of Classical Electrodynamics, Physics Letters, 8, 3, (1964), p. 185-187. (in English, shorter but presents the same core idea)

[URL]http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9163(64)91989-4[/URL]

“I don’t see what Medina’s paper (linked by Vanhees) has to do with discrete spacetime. It just posits that a classical field theory can acommodate matter bodies (meeting criteria determined by the field theory), but not point particles.”

I was responding to the initial thoughts in this Insight: “In these posts, we’re seeing how our favorite theories of physics deal with the idea that space and time are a continuum, with points described as lists of real numbers. We’re not asking if this idea is true: there’s no clinching evidence to answer that question, so it’s too easy to let ones philosophical prejudices choose the answer. Instead, we’re looking to see what problems this idea causes, and how physicisists have struggled to solve them.”

“But is a discrete spacetime a credible alternative? Can we formulate the known laws of physics in a discrete spacetime? Currently, the answer seems to be “no”, as there is no consensus lattice standard model because of the problem of chiral fermions interacting with non-Abelian gauge fields.”

I don’t see what Medina’s paper (linked by Vanhees) has to do with discrete spacetime. It just posits that a classical field theory can acommodate matter bodies (meeting criteria determined by the field theory), but not point particles.

The summary of radiation reaction and point charges is very helpful — I hadn’t heard of a lot of the more recent work. A question that’s been bothering me for a long time is whether there is any sense in which one can prove that a system of charged particles can’t be stable. This seems to be something that all physicists are convinced must be true, but that nobody knows how to prove, or even how to state rigorously. Acceleration is a necessary but not sufficient condition for radiation, so one can’t just declare that such a system automatically radiates away its energy to infinity. It’s conceivable that for a set of initial conditions of measure zero, radiation vanishes exactly and the system is stable. One would have to prove that this doesn’t happen. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem possible even to get started on such a proof, because there just isn’t any satisfactory, canonical, self-consistent theory of interacting point charges.

But is a discrete spacetime a credible alternative? Can we formulate the known laws of physics in a discrete spacetime? Currently, the answer seems to be “no”, as there is no consensus lattice standard model because of the problem of chiral fermions interacting with non-Abelian gauge fields.

Great overview of the “radiation-reaction problem”, but isn’t the conclusion rather that point charges in the literal sense are still strangers to classical field theory? For “particles” of “finite extent”, there seem not to be any problems. See, e.g., the paper

Medina, Rodrigo. “Radiation reaction of a classical quasi-rigid extended particle.” Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 39.14 (2006): 3801.

[URL]http://stacks.iop.org/JPhysA/39/3801[/URL]

[URL]http://arxiv.org/pdf/physics/0508031[/URL]

Great series John!

Thanks John, really exciting posts!

I can't imagine more understandable explanations even if I don't understand a lot of them :)There's a full version of the janssen paper at:https://netfiles.umn.edu/users/janss011/home%20page/electron.pdfHNY

The link to the Feynman lectures is slightly broken: the backslash in it should not be there.

I think this paper, 'A rigorous derivation of electromagnetic self force' by Gralla, Hart and Wald, is relevant here (cited 76 times). http://lanl.arxiv.org/abs/0905.2391

Very interesting article. For those interested, my friend James Hedberg, now at the City University of New York, wrote a historical/theoretical overview of fieldless E&M.http://www.jameshedberg.com/docs/directactionelectrodynamics.pdf