imsmooth

- 154

- 13

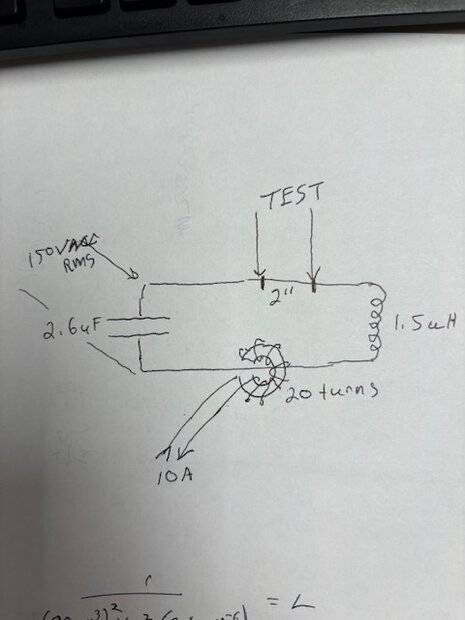

I want to measure tank circuit currents using *different* methods. Below is the tank circuit. The coupling transformer has 20 turns and has 10A @ 80khz going through it. This means there should be a maximum of 200A in the tank (20:1 turns ratio). I measure the voltage across the 2.6uF capacitor and get about 150 Vrms. With a capacitative reactance of about 0.75R this equals 200A.

I now want to measure the voltage across 1 inch (25.4mm) of the 1/2" copper tubing (TEST, mislabeled as 2") that serves as the conductor for the tank. The tubing has an outside diameter of 15.975mm. With a skin effect of .2mm @80kHz I get:

R = p*L/A

A = pi/4 * (15.875^2 - 15.475^2)

L = 0.0254m, A = 0.00000984m^2, p = 1.7x10-8 R-m

This gives R = 0.000044R

When I measure the voltage across 1 inch of pipe under the same conditions I get 3.4Vrms.

A = V/R which would be over 700,000A. This can not be correct. What am I missing?

NOTE: voltage measurements are done with oscilloscope

I now want to measure the voltage across 1 inch (25.4mm) of the 1/2" copper tubing (TEST, mislabeled as 2") that serves as the conductor for the tank. The tubing has an outside diameter of 15.975mm. With a skin effect of .2mm @80kHz I get:

R = p*L/A

A = pi/4 * (15.875^2 - 15.475^2)

L = 0.0254m, A = 0.00000984m^2, p = 1.7x10-8 R-m

This gives R = 0.000044R

When I measure the voltage across 1 inch of pipe under the same conditions I get 3.4Vrms.

A = V/R which would be over 700,000A. This can not be correct. What am I missing?

NOTE: voltage measurements are done with oscilloscope

Last edited by a moderator: