zenterix

- 774

- 84

- Homework Statement

- I am a little confused about some calculations in some notes introducing the concept of an RLC series circuit.

- Relevant Equations

- Below I go through the reasoning in the notes.

The notes are in an attached pdf on pages 10-13.

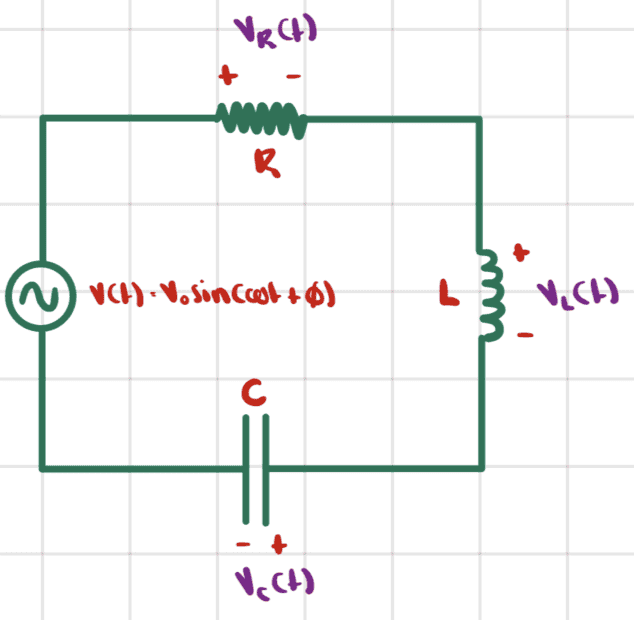

We start with the driven RLC circuit below

The AC source voltage is ##V(t)=V_0\sin{(\omega t +\phi)}## and we would like to find the current ##I(t)=I_0\sin{(\omega t)}##.

Using Faraday's law we have

$$V(t)-V_R(t)-V_C(t)=L\dot{I}=V_L(t)\tag{1}$$

$$V_0\sin{(\omega t+\phi)}-IR-\frac{Q}{C}=L\dot{I}\tag{2}$$

After some algebra and differentiation we obtain the following differential equation

$$\ddot{I}+\frac{R}{L}\dot{I}+\frac{1}{LC}I=\frac{V_0\omega}{L}\cos{(\omega t+\phi)}\tag{3}$$

This particular electromagnetism course doesn't assume the student has taken differential equations. It seems that for this reason they sometimes find solutions in a way that involves intuition rather than standard methods.

My question in this post is about how they are solving it in these notes.

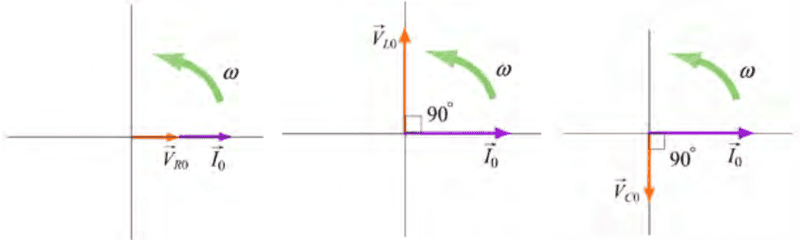

First they consider the instantaneous voltages across the resistor, the inductor, and the capacitor.

Here are the phasor diagrams for the relationships between current and voltage in these three circuit elements.

For the record, phasor diagrams are new to me.

I think I just need to be explicitly told why the phasors are the same in those three previous circuits as they are in the current circuit. Is it superposition because each circuit element is linear?

It is also not clear why we can justify going from (1) to (4).

After this, it is simple to obtain an expression for the amplitude of the current.

We simply look at the rhs plot above and compute ##V_0## using Pythagorean theorem.

Now, I found the notation used a bit confusing, let me try to clarify.

Let

$$I_{R0}=\frac{1}{X_R}V_{R0}\tag{4}$$

$$I_{C0}=\frac{1}{X_C}V_{C0}\tag{5}$$

$$I_{L0}=\frac{1}{X_L}V_{L0}\tag{6}$$

where ##X_R, X_C##, and ##X_L## are resistive, capacitive, and inductive reactances.

These three expressions simply relate current and voltage amplitudes for three separate circuits, each with an AC source and a single circuit element (a resistor, a capacitor, and an inductor, respectively).

$$X_R=R\tag{7}$$

$$X_C=\frac{1}{\omega C}\tag{8}$$

$$X_L=\omega L\tag{9}$$

So again, from the rhs plot above, we get

$$V_0=I_0\sqrt{X_R^2+(X_L-X_C)^2}\tag{10}$$

and so the amplitude of the current is

$$I_0=\frac{V_0}{\sqrt{X_R^2+(X_L-X_C)^2}}\tag{11}$$

From the same rhs plot above we can determine that the phase constant satisfies

$$\tan{(\phi)}=\frac{1}{R}\left ( \omega L-\frac{1}{\omega L}\right )\tag{12}$$

Therefore the phase constant is

$$\phi=\tan^{-1} \frac{1}{R}\left ( \omega L-\frac{1}{\omega L}\right )\tag{13}$$

In the next post I show how I went about solving the differential equation (3).

We start with the driven RLC circuit below

The AC source voltage is ##V(t)=V_0\sin{(\omega t +\phi)}## and we would like to find the current ##I(t)=I_0\sin{(\omega t)}##.

Using Faraday's law we have

$$V(t)-V_R(t)-V_C(t)=L\dot{I}=V_L(t)\tag{1}$$

$$V_0\sin{(\omega t+\phi)}-IR-\frac{Q}{C}=L\dot{I}\tag{2}$$

After some algebra and differentiation we obtain the following differential equation

$$\ddot{I}+\frac{R}{L}\dot{I}+\frac{1}{LC}I=\frac{V_0\omega}{L}\cos{(\omega t+\phi)}\tag{3}$$

This particular electromagnetism course doesn't assume the student has taken differential equations. It seems that for this reason they sometimes find solutions in a way that involves intuition rather than standard methods.

My question in this post is about how they are solving it in these notes.

First they consider the instantaneous voltages across the resistor, the inductor, and the capacitor.

Here are the phasor diagrams for the relationships between current and voltage in these three circuit elements.

For the record, phasor diagrams are new to me.

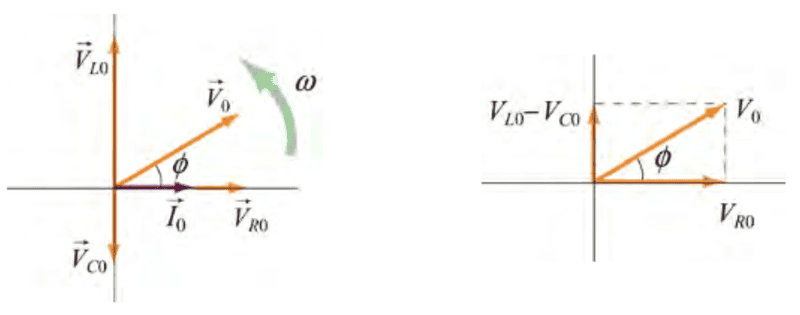

Using the phasor representation, Eq. (1) can be written as

$$\vec{V}_0=\vec{V}_{R0}+\vec{V}_{L0}+\vec{V}_{C0}\tag{4}$$

as shown in the next figure

I understand this last paragraph on some level because before analyzing the current circuit, I analyzed three different circuits: an AC source with just a resistor, with just an inductor, and with just a capacitor.Again we see that current phasor ##\vec{I}_0## leads the capacitive voltage phasor ##\vec{V}_{C0}## by ##\pi/2## but lags the inductive voltage phasor ##\vec{V}_{L0}## by ##\pi/2##.

The three voltage phasors rotate counterclockwise as time increases, with their relative positions fixed.

I think I just need to be explicitly told why the phasors are the same in those three previous circuits as they are in the current circuit. Is it superposition because each circuit element is linear?

It is also not clear why we can justify going from (1) to (4).

After this, it is simple to obtain an expression for the amplitude of the current.

We simply look at the rhs plot above and compute ##V_0## using Pythagorean theorem.

Now, I found the notation used a bit confusing, let me try to clarify.

Let

$$I_{R0}=\frac{1}{X_R}V_{R0}\tag{4}$$

$$I_{C0}=\frac{1}{X_C}V_{C0}\tag{5}$$

$$I_{L0}=\frac{1}{X_L}V_{L0}\tag{6}$$

where ##X_R, X_C##, and ##X_L## are resistive, capacitive, and inductive reactances.

These three expressions simply relate current and voltage amplitudes for three separate circuits, each with an AC source and a single circuit element (a resistor, a capacitor, and an inductor, respectively).

$$X_R=R\tag{7}$$

$$X_C=\frac{1}{\omega C}\tag{8}$$

$$X_L=\omega L\tag{9}$$

So again, from the rhs plot above, we get

$$V_0=I_0\sqrt{X_R^2+(X_L-X_C)^2}\tag{10}$$

and so the amplitude of the current is

$$I_0=\frac{V_0}{\sqrt{X_R^2+(X_L-X_C)^2}}\tag{11}$$

From the same rhs plot above we can determine that the phase constant satisfies

$$\tan{(\phi)}=\frac{1}{R}\left ( \omega L-\frac{1}{\omega L}\right )\tag{12}$$

Therefore the phase constant is

$$\phi=\tan^{-1} \frac{1}{R}\left ( \omega L-\frac{1}{\omega L}\right )\tag{13}$$

In the next post I show how I went about solving the differential equation (3).

Attachments

Last edited: