zenterix

- 774

- 84

- TL;DR Summary

- There is a small section in the book "Special Relativity" by Anthony Philip French that has me bewildered for quite a few hours now.

I'd like to understand how to obtain equation (2) below.

**My question is how to obtain (2)?**

**Here is my attempt to answer this question (which runs into an obstacle)**

Suppose we have a telescope on earth with air inside the tube (instead of water) and around the telescope.

Consider two frames: ##S##, which is approximately at rest relative to a very distant star, and frame ##S'##, earth's frame.

As a side note on notation: I will write things like ##\vec{v}_{S',S}## to denote the velocity vector of frame ##S'## relative to frame ##S##, or ##\vec{v}_{l,S'}## to denote the velocity vector of light relative to frame ##S'##.

The earth orbits the sun. At any point in this orbit, from the point of view of frame ##S##, we can consider that the rays of light coming from the star incide with the same velocity vector ##\vec{v}_{l,S}## (that is, this velocity has the same angle ##\theta## relative to the plane of orbit and comes from the same direction always).

Earth has a velocity vector ##\vec{v}_{S',S}## relative to frame ##S## at each point in its orbit and we can decompose this into a component parallel to the projection of ##\vec{v}_{l,S}## onto the orbital plane and a component perpendicular to this projection.

(Note that we are not considering the earth's rotation)

If we consider just the parallel component for now, it can be shown that if this parallel component is not zero, then the velocity vector of light relative to earth, ##\vec{v}_{l,S'}## makes an angle ##\alpha## different from ##\theta## to the orbital plane.

It can be shown that the difference ##\theta-\alpha##, which we call the aberration angle, is given by

$$\theta - \alpha \approx \sin{\theta}\frac{v_{S',S}}{c}$$

What this result tells us is that we have to tilt a microscope "forward", ie towards the horizontal to see the star through the telescope.

(Note that, as I mentioned before, we are only considering one component of the velocity of the earth; if we consider the other component, we will also have to have a tilt in that direction as well)

**Now let's consider what happens when we fill the telescope's tube with water**. If there were no refraction (but the speed of light were still reduced in water), then the aberration angle would now be

$$\theta-\alpha=\sin{\theta}\frac{v_{S',S}}{c/n}\tag{3}$$

$$=n\sin{\theta}\frac{v_{S',S}}{c}\tag{4}$$

and so for a refractive index larger than 1, we would have a larger aberration angle than before, ie we would have to tilt the microscope even more.

However, we do have refraction.

**This is the point at which I start having difficulty.**

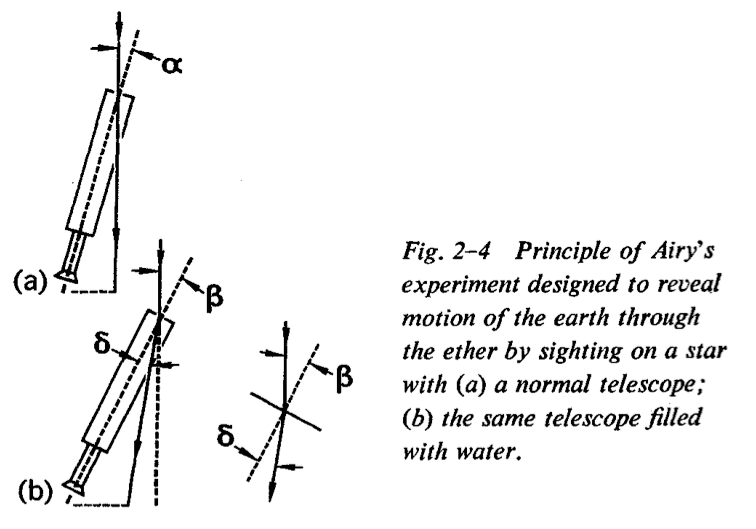

##\beta## is the angle shown in figure 2-4b above.

This angle is the aberration angle for an incidence angle of ##90^{\circ}##.

We see a solid line showing light inciding at this ##90^{\circ}## angle with the horizontal and being refracted.

There is also a dotted line passing straight through the middle of the telescope. Whatever the position of the telescope, if we are in frame ##S'##and if light hits the telescope at this right angle (relative to the border of the telescope) the light will not bend.

However, though we can vary the position of the telescope, the angle at which light arrives at the telescope depends on the speeds of light and earth. In particular, if we measure the angle from the vertical, then (3) and (4) tell us what this angle is. This is what ##\beta## is.

In particular, if ##\theta=90^{\circ}##, then

$$\beta=\theta-\alpha=\frac{v_{S',S}}{c/n_{\text{water}}}\tag{5}$$

Snell's law tells us that

$$n_{\text{air}}\sin{\beta}=n_{\text{water}}\sin{\delta}\tag{6}$$

$$n_{\text{water}}=n_{\text{air}}\frac{\sin{\beta}}{\sin{\delta}}\approx \frac{\beta}{\delta}$$

The book says that the condition for centering the star's image in the telescope is (2), which I repeat here

$$\delta\approx\frac{v}{c/n}=\frac{nv}{c}\tag{2}$$

At this point, I am going to stop, because I have spent three hours formulating this post and I don't know how to proceed further. That is, I have written some equations above, but I can not reconcile them with (2).

Suppose that a telescope has been aimed at a star whose true direction

is at ##90^{\circ}## to the plane of the earth's orbit. Let the unknown aberration angle > be a [Fig. 2-4(a)] and let the unknown speed of

the earth through the ether be ##v##. Now imagine that the whole tube of

the telescope is filled with water, of refractive index ##n##. Since

light travels more slowly in water than in air or vacuum, the time for

the light to travel down the length of the telescope tube will be

lengthened—by the factor ##n##. One might expect, therefore, that to

keep the star's image in the center of the field of view one would have to till the telescope further, to some new aberration angle

##\beta##, and that the amount of this adjustment could be used to find

the speed $v$. At first glance one might think that the angle ##\beta##

would be just ##nv/c##, but in analyzing this experiment one must

remember that, because the objective lens of the telescope now has air

on one side and water on the other, the light rays entering the

telescope are bent toward the axis of the instrument, as indicated in Fig. 2-4(b). Inside the telescope we would expect the rays to travel at an angle ##\delta## to the axis such that

$$n=\frac{\sin{\beta}}{\sin{\delta}}\approx\frac{\beta}{\delta}\tag{1}$$

Since the light is traveling downward with speed ##c/n##, and the telescope is moving sideways at speed ##v##, the condition for centering

the star's image in the telescope is

$$\delta\approx\frac{v}{c/n}=\frac{nv}{c}\tag{2}$$

**My question is how to obtain (2)?**

**Here is my attempt to answer this question (which runs into an obstacle)**

Suppose we have a telescope on earth with air inside the tube (instead of water) and around the telescope.

Consider two frames: ##S##, which is approximately at rest relative to a very distant star, and frame ##S'##, earth's frame.

As a side note on notation: I will write things like ##\vec{v}_{S',S}## to denote the velocity vector of frame ##S'## relative to frame ##S##, or ##\vec{v}_{l,S'}## to denote the velocity vector of light relative to frame ##S'##.

The earth orbits the sun. At any point in this orbit, from the point of view of frame ##S##, we can consider that the rays of light coming from the star incide with the same velocity vector ##\vec{v}_{l,S}## (that is, this velocity has the same angle ##\theta## relative to the plane of orbit and comes from the same direction always).

Earth has a velocity vector ##\vec{v}_{S',S}## relative to frame ##S## at each point in its orbit and we can decompose this into a component parallel to the projection of ##\vec{v}_{l,S}## onto the orbital plane and a component perpendicular to this projection.

(Note that we are not considering the earth's rotation)

If we consider just the parallel component for now, it can be shown that if this parallel component is not zero, then the velocity vector of light relative to earth, ##\vec{v}_{l,S'}## makes an angle ##\alpha## different from ##\theta## to the orbital plane.

It can be shown that the difference ##\theta-\alpha##, which we call the aberration angle, is given by

$$\theta - \alpha \approx \sin{\theta}\frac{v_{S',S}}{c}$$

What this result tells us is that we have to tilt a microscope "forward", ie towards the horizontal to see the star through the telescope.

(Note that, as I mentioned before, we are only considering one component of the velocity of the earth; if we consider the other component, we will also have to have a tilt in that direction as well)

**Now let's consider what happens when we fill the telescope's tube with water**. If there were no refraction (but the speed of light were still reduced in water), then the aberration angle would now be

$$\theta-\alpha=\sin{\theta}\frac{v_{S',S}}{c/n}\tag{3}$$

$$=n\sin{\theta}\frac{v_{S',S}}{c}\tag{4}$$

and so for a refractive index larger than 1, we would have a larger aberration angle than before, ie we would have to tilt the microscope even more.

However, we do have refraction.

**This is the point at which I start having difficulty.**

##\beta## is the angle shown in figure 2-4b above.

This angle is the aberration angle for an incidence angle of ##90^{\circ}##.

We see a solid line showing light inciding at this ##90^{\circ}## angle with the horizontal and being refracted.

There is also a dotted line passing straight through the middle of the telescope. Whatever the position of the telescope, if we are in frame ##S'##and if light hits the telescope at this right angle (relative to the border of the telescope) the light will not bend.

However, though we can vary the position of the telescope, the angle at which light arrives at the telescope depends on the speeds of light and earth. In particular, if we measure the angle from the vertical, then (3) and (4) tell us what this angle is. This is what ##\beta## is.

In particular, if ##\theta=90^{\circ}##, then

$$\beta=\theta-\alpha=\frac{v_{S',S}}{c/n_{\text{water}}}\tag{5}$$

Snell's law tells us that

$$n_{\text{air}}\sin{\beta}=n_{\text{water}}\sin{\delta}\tag{6}$$

$$n_{\text{water}}=n_{\text{air}}\frac{\sin{\beta}}{\sin{\delta}}\approx \frac{\beta}{\delta}$$

The book says that the condition for centering the star's image in the telescope is (2), which I repeat here

$$\delta\approx\frac{v}{c/n}=\frac{nv}{c}\tag{2}$$

At this point, I am going to stop, because I have spent three hours formulating this post and I don't know how to proceed further. That is, I have written some equations above, but I can not reconcile them with (2).