Lambda96

- 233

- 77

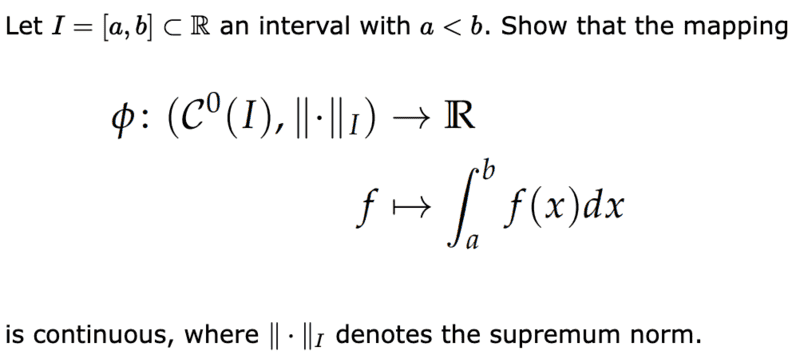

- Homework Statement

- Show that the mapping ##\phi## is continuous

- Relevant Equations

- none

Hi,

I don't know if I have solved task correctly

I used the epsilon-delta definition for the proof, so it must hold for ##f,g \in (C^0(I), \| \cdot \|_I)## ##\sup_{x \in [a,b]} |F(x)-G(x)|< \delta \longrightarrow \quad |\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx - \int_{a}^{b} g(x)dx |< \epsilon##

I then proceeded as follows

##|\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx - \int_{a}^{b} g(x)dx | =|F(b)-F(a)-G(b)+G(a)|=|F(b)-G(b)+G(a)-F(a)|##

Then I used the supremum norm to estimate the above expression ##|F(b)-F(a)-G(b)+G(a)|=|F(b)-G(b)+G(a)-F(a)| \le \sup_{x \in [a,b]} |F(x)-G(x)|+\sup_{x \in [a,b]} |F(x)-G(x)|+\sup_{x \in [a,b]} |G(x)-F(x)|=2\sup_{x \in [a,b]} |F(x)-G(x)|<2\delta## it then follows that ##\delta## must be defined as follows ##\delta= \frac{\epsilon}{2} ##

I don't know if I have solved task correctly

I used the epsilon-delta definition for the proof, so it must hold for ##f,g \in (C^0(I), \| \cdot \|_I)## ##\sup_{x \in [a,b]} |F(x)-G(x)|< \delta \longrightarrow \quad |\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx - \int_{a}^{b} g(x)dx |< \epsilon##

I then proceeded as follows

##|\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx - \int_{a}^{b} g(x)dx | =|F(b)-F(a)-G(b)+G(a)|=|F(b)-G(b)+G(a)-F(a)|##

Then I used the supremum norm to estimate the above expression ##|F(b)-F(a)-G(b)+G(a)|=|F(b)-G(b)+G(a)-F(a)| \le \sup_{x \in [a,b]} |F(x)-G(x)|+\sup_{x \in [a,b]} |F(x)-G(x)|+\sup_{x \in [a,b]} |G(x)-F(x)|=2\sup_{x \in [a,b]} |F(x)-G(x)|<2\delta## it then follows that ##\delta## must be defined as follows ##\delta= \frac{\epsilon}{2} ##