Nova_Chr0n0

- 16

- 3

- Homework Statement

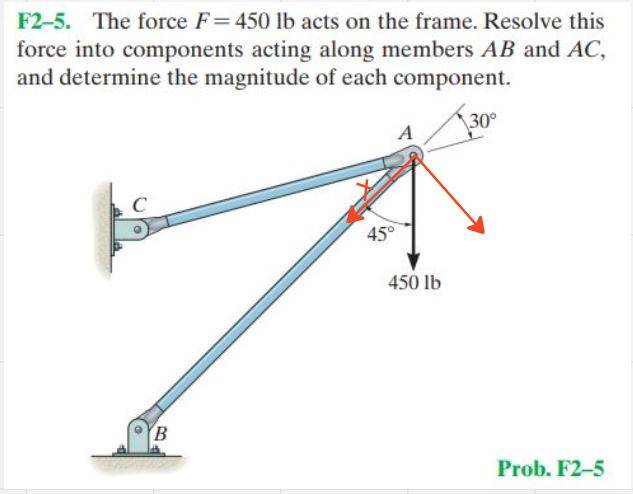

- The force F = 450 lb acts on the frame. Resolve this force into components acting along members AB and AC, and determine the magnitude of each component. (Figure is attached below)

- Relevant Equations

- N/A

I've already got the answer and the way to solve it (parallelogram), but I'm just wondering why I cannot use the technique I've learned in the lesson torque.

Let's focus on the line AB, if I use what I've learned in torque, the components would be like this:

To find the force component in AB, I could just solve my assign variable "x" and use trigonometry. In this scenario I would have

x = AB = 450cos(45)

But this answer is incorrect and is not similar to when I use the parallelogram method. My question is, what is the difference between them? Is the technique only for torque/moment problems?

Let's focus on the line AB, if I use what I've learned in torque, the components would be like this:

To find the force component in AB, I could just solve my assign variable "x" and use trigonometry. In this scenario I would have

x = AB = 450cos(45)

But this answer is incorrect and is not similar to when I use the parallelogram method. My question is, what is the difference between them? Is the technique only for torque/moment problems?