lovex25

- 2

- 0

[solved]Find volume of solid generated (Calc 2)

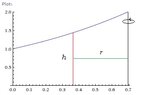

Find the volume of the solid generated by revolving the region in the first quadrant bounded by the coordinate axes, the curve y=e^x, and the line x = ln 2 about the line x= ln 2.

So I tried graphing it to see visually, and the expression I got for calculating the volume was ∫π(ln2-lny)^2dy, evaluating from 0 to 2 using disk method, and the answer I got was 4π, but apparently that doesn't match the answer in the back of the book. I'd really appreciate if someone can help me out!

http://img844.imageshack.us/img844/9792/xll8.jpg

Off topic: First time posting a thread here, may I ask how do you type the mathematical symbols such as the integral sign and whatnot, or do I have to manually copy and paste from other website?

Find the volume of the solid generated by revolving the region in the first quadrant bounded by the coordinate axes, the curve y=e^x, and the line x = ln 2 about the line x= ln 2.

So I tried graphing it to see visually, and the expression I got for calculating the volume was ∫π(ln2-lny)^2dy, evaluating from 0 to 2 using disk method, and the answer I got was 4π, but apparently that doesn't match the answer in the back of the book. I'd really appreciate if someone can help me out!

http://img844.imageshack.us/img844/9792/xll8.jpg

Off topic: First time posting a thread here, may I ask how do you type the mathematical symbols such as the integral sign and whatnot, or do I have to manually copy and paste from other website?

Last edited: