RonWerner

- 2

- 1

- TL;DR Summary

- 2 magnets start being attracted to each other and will increase speed until colliding. What can I say about the force/accelleration/speed?

Sorry, I guess I should have remembered all of this from my school days, but right now I have forgotten so much that I need some help.

I am developing some simple experiments for school children (age ca. 12). This one involving magnets.

I am not asking for detailed calculations, that is way beyond the scope of this experiment. I need some help with NOT saying stupid things.

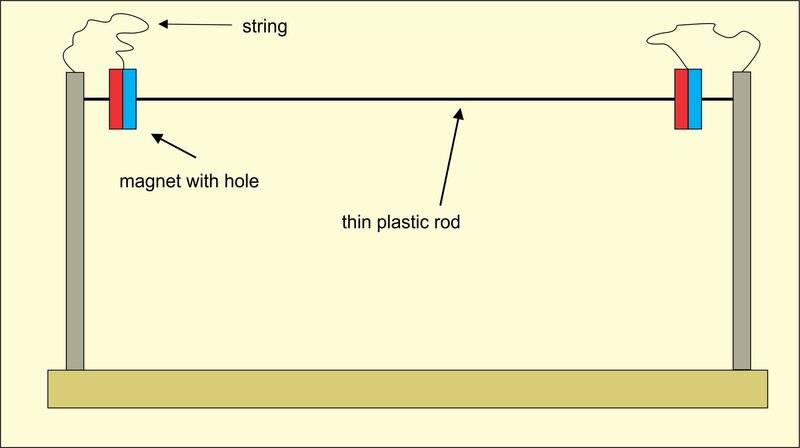

The plan is to make some simple device with 2 strong neodymium magnets, attracted to each other, with increasingly high speed, but not exactly colliding, as that would potentially damage the magnets.

What can I say about the speed of the moving magnets? What about the accelleration? What about the force?

Put it this way: what can I say for every centimeter the magnets come closer to each other? What kind of mathematical relationship is there? Is there a linear or exponential relationship?

Hopefully somebody can help me to some simple answers! Thanks in advance!

Ron Werner

Norway

I am developing some simple experiments for school children (age ca. 12). This one involving magnets.

I am not asking for detailed calculations, that is way beyond the scope of this experiment. I need some help with NOT saying stupid things.

The plan is to make some simple device with 2 strong neodymium magnets, attracted to each other, with increasingly high speed, but not exactly colliding, as that would potentially damage the magnets.

What can I say about the speed of the moving magnets? What about the accelleration? What about the force?

Put it this way: what can I say for every centimeter the magnets come closer to each other? What kind of mathematical relationship is there? Is there a linear or exponential relationship?

Hopefully somebody can help me to some simple answers! Thanks in advance!

Ron Werner

Norway