- #1

sergiokapone

- 302

- 17

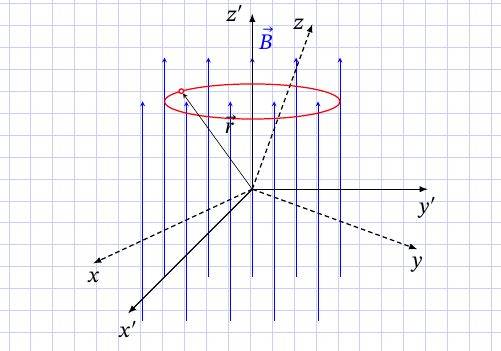

Hi all, I interested in how can I get low of motion in for orbiting particle in a uniform magnetic field

$$\frac{d\vec{r}}{dt} = \vec{\omega}\times\vec{r},\qquad

\vec{\omega} = \frac{e\vec{B}}{mc},$$

Of course, rotating about z' axis is very simple.

\begin{equation}\label{eq:K}

\begin{cases}

x' = R\cos(\omega_{z'} t ), \\

y' = R\sin(\omega_{z'} t ), \\

z' = z'_0.

\end{cases}

\end{equation}

But what can I do, when axes is arbitrary oriented?

$$\frac{d\vec{r}}{dt} = \vec{\omega}\times\vec{r},\qquad

\vec{\omega} = \frac{e\vec{B}}{mc},$$

Of course, rotating about z' axis is very simple.

\begin{equation}\label{eq:K}

\begin{cases}

x' = R\cos(\omega_{z'} t ), \\

y' = R\sin(\omega_{z'} t ), \\

z' = z'_0.

\end{cases}

\end{equation}

But what can I do, when axes is arbitrary oriented?

Last edited: