Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Matej Bresar's book, "Introduction to Noncommutative Algebra" and am currently focussed on Chapter 1: Finite Dimensional Division Algebras ... ...

I need help with the proof of Lemma 1.24 ...

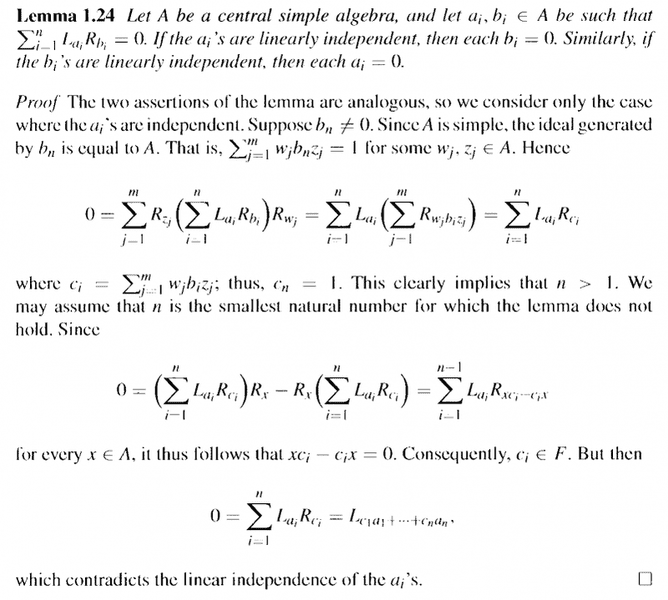

Lemma 1.24 reads as follows:

My questions regarding the proof of Lemma 1.24 are as follows ... ...Question 1

In the above proof by Bresar, we read:

" ... ... Since ##A## is simple, the ideal generated by ##b_n## is equal to ##A##.

That is ##\sum_{ j = 1 }^m w_j b_n z_j = 1## for some ##w_j , z_J \in A##. ... ... "My question is ... ... how/why does the fact that the ideal generated by ##b_n## being equal to ##A## ...

imply that ... ##\sum_{ j = 1 }^m w_j b_n z_j = 1## for some ##w_j , z_J \in A## ...?

Question 2In the above proof by Bresar, we read:" ... ##0 = \sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ z_j } \ ( \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } R_{ b_i } ) \ R_{ w_j }####= \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } \ ( \sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ w_j b_i z_j } )####= \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } R_{ c_i }##... ... "

My questions are

(a) can someone help me to understand how##\sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ z_j } \ ( \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } R_{ b_i } ) \ R_{ w_j }####= \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } \ ( \sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ w_j b_i z_j } ) ##

(b) can someone help me to understand how##\sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } \ ( \sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ w_j b_i z_j } ) ####= \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } R_{ c_i }##

Help will be appreciated ...

Peter

=========================================================================

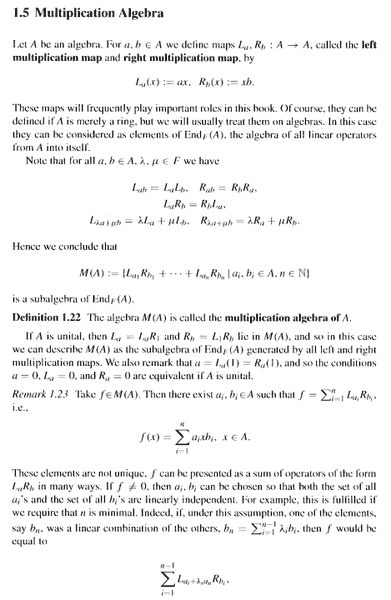

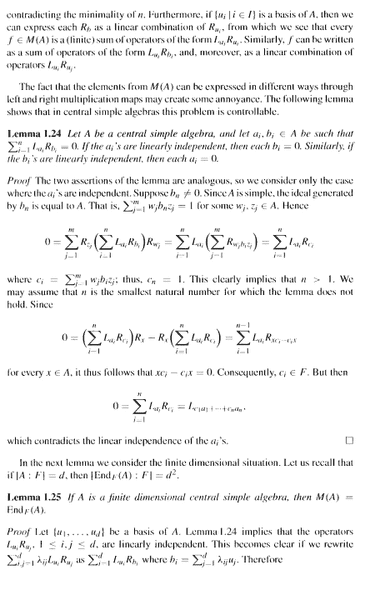

*** NOTE ***So that readers of the above post will be able to understand the context and notation of the post ... I am providing Bresar's first two pages on Multiplication Algebras ... ... as follows:

I need help with the proof of Lemma 1.24 ...

Lemma 1.24 reads as follows:

My questions regarding the proof of Lemma 1.24 are as follows ... ...Question 1

In the above proof by Bresar, we read:

" ... ... Since ##A## is simple, the ideal generated by ##b_n## is equal to ##A##.

That is ##\sum_{ j = 1 }^m w_j b_n z_j = 1## for some ##w_j , z_J \in A##. ... ... "My question is ... ... how/why does the fact that the ideal generated by ##b_n## being equal to ##A## ...

imply that ... ##\sum_{ j = 1 }^m w_j b_n z_j = 1## for some ##w_j , z_J \in A## ...?

Question 2In the above proof by Bresar, we read:" ... ##0 = \sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ z_j } \ ( \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } R_{ b_i } ) \ R_{ w_j }####= \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } \ ( \sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ w_j b_i z_j } )####= \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } R_{ c_i }##... ... "

My questions are

(a) can someone help me to understand how##\sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ z_j } \ ( \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } R_{ b_i } ) \ R_{ w_j }####= \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } \ ( \sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ w_j b_i z_j } ) ##

(b) can someone help me to understand how##\sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } \ ( \sum_{ j = 1 }^m R_{ w_j b_i z_j } ) ####= \sum_{ i = 1 }^n L_{ a_i } R_{ c_i }##

Help will be appreciated ...

Peter

=========================================================================

*** NOTE ***So that readers of the above post will be able to understand the context and notation of the post ... I am providing Bresar's first two pages on Multiplication Algebras ... ... as follows:

Attachments

Last edited: