- #1

Michel

- 15

- 0

Hello,

I have a question regarding the density of the LHC vs. Cosmic Rays and why the big difference doesn't matter for particle research? As a reference we look at ultra-high-energy cosmic rays which are perfect for 'one on one' collisions, but isn't 'dosage' also a parameter to consider?

--

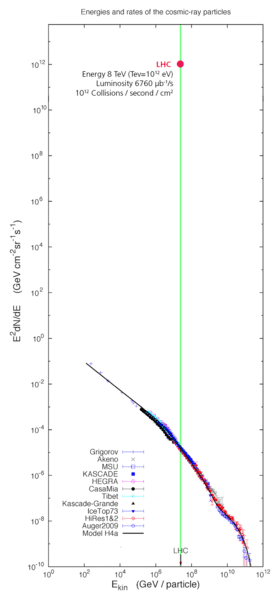

In nature there are about a thousand cosmic ray collisions of a few GeV’s (1 GeV= 109 electron Volt) per second per m2. In LHC it are about one 1 billion per second per cm2. That’s 1.000.000 times more for an area which is 10.000 smaller. It is a density difference of 10 billion and unique in the Universe. (see graph)

The upgraded LHC is going to generate collisions are 1000 times more intense, with energies of 13 TeV (1 TeV= 1012 eV). These collisions are in nature even less frequent per m2 while the density at the LHC of 10 billion per cm2 will be maintained.

--

Protons are not only tiny 'stand alone' particles but also wider energy fields connected to the Higgs Field. When cramping a lot of matter/energy in a small box of just a couple millimeters, than there is a different situation in the lab than for cosmic rays in nature whom have a far less dense distribution.

We see it everywhere in science that dosage plays a key role, except for particle collisions where it is never considered of any importance, why? Are the distances in between (follow up) collisions relatively so spaced out or are there studies of what the limits are of the numbers of collisions one may jam into a particular volume? Also does the 'collision box' gets to be heat up after a while or does everything just fly by? The LHC creates temperatures 105 times hotter than the center of the sun, how much of this energy is spread out through the Higgs Field onto the surrounding matter?

Regards,

Michel

I have a question regarding the density of the LHC vs. Cosmic Rays and why the big difference doesn't matter for particle research? As a reference we look at ultra-high-energy cosmic rays which are perfect for 'one on one' collisions, but isn't 'dosage' also a parameter to consider?

--

In nature there are about a thousand cosmic ray collisions of a few GeV’s (1 GeV= 109 electron Volt) per second per m2. In LHC it are about one 1 billion per second per cm2. That’s 1.000.000 times more for an area which is 10.000 smaller. It is a density difference of 10 billion and unique in the Universe. (see graph)

The upgraded LHC is going to generate collisions are 1000 times more intense, with energies of 13 TeV (1 TeV= 1012 eV). These collisions are in nature even less frequent per m2 while the density at the LHC of 10 billion per cm2 will be maintained.

--

Protons are not only tiny 'stand alone' particles but also wider energy fields connected to the Higgs Field. When cramping a lot of matter/energy in a small box of just a couple millimeters, than there is a different situation in the lab than for cosmic rays in nature whom have a far less dense distribution.

We see it everywhere in science that dosage plays a key role, except for particle collisions where it is never considered of any importance, why? Are the distances in between (follow up) collisions relatively so spaced out or are there studies of what the limits are of the numbers of collisions one may jam into a particular volume? Also does the 'collision box' gets to be heat up after a while or does everything just fly by? The LHC creates temperatures 105 times hotter than the center of the sun, how much of this energy is spread out through the Higgs Field onto the surrounding matter?

Regards,

Michel