- #1

sbpf

- 3

- 0

A thought crossed my mind about the idea of atomic computers. In short, I have no clue as to whether such a thing is feasible, already in the works, or just a bunch of nonsense, which is why I decided to bring it up here and see if anyone could offer some insight into this idea. If so, I’d greatly appreciate it. Below are just some of my thoughts on the subject.

From what I understand, today's digital computers rely on transistors, which in turn act as switches that relay two possible states, that is, on or off. Based on this, we know that at their most basic level, computers understand sequences of bits which represent instructions or operations for the processor to perform. Now, what if there was a way to relay that information in a much faster way?

Note: The explanation I’m using to model the inner workings of an atomic computer uses 2 atoms, but could use any arrangement of 1 or more particles that aren’t necessarily atoms. I also make a fair amount of assumptions about the data we can gather from them.

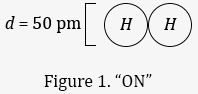

First, suppose we have an enclosure which consists of two atoms—in this case Hydrogen, whose diameter is roughly 50 picometers (50×10-12 m)—sitting side by side so we can say they're almost touching. Also suppose we can determine almost instantly whether the two atoms are close enough. Then, let this represent a state of on or 1.

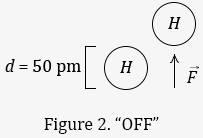

Next, suppose we can generate a field or force ##\vec{F}## that will displace a (possibly charged) Hydrogen atom a sufficient distance away so that we may similarly call this state off or 0.

Finally, suppose we can vary the ##\vec{F}## field/force such that the Hydrogen atom moves back to its initial on position. This completes an entire cycle for which there are only two possible states.

For posterity and simplicity, let's suppose we can accelerate these atoms at or near the speed of light. From this, we shall calculate the frequency at which this machine can process individual bits of information.

Perhaps one day we'll reach the conclusion that a system with two possible states is surely the simplest one, but probably not the most efficient one. Indeed, the ability to represent information in more states than 2 can lead to an exponential rise in the amount of information we can gather and process at any given time. In light of this, also consider the possibility that the atoms in this design could represent numerous different states, then data could be ascertained about their atomic states and transmitted in much larger segments at any given time. Examples of information that could be used to represent multiple states include charge distribution, attraction/repulsion and distance, among others. It's also understood that working at the atomic level introduces issues of accuracy and precision; however, by establishing an absolute minimum and maximum that are well within a proven range of tolerance for the data we can gather, and scaling it down to a finite number of states, we can drastically reduce the possibility for error.

Clearly though, the premise behind quantum computers holds the most benefit by far, but the field is still very young. Although atomic computers would never supplant quantum computers, it could very well produce more tangible, short-term benefits over today's technology. A joke at the expense of quantum computers: The quantum superposition principle as it’s applied to quantum computing is quite appealing from a computer scientist's point of view; that is, sorting algorithms can now assume that data must already be in sorted order (since it can exist in all of its possible states simultaneously), therefore no sort is needed. The problem only arises when we actually try looking at it…

But getting back to the reason I created this post, I really enjoy thinking about these kinds of things, but many times I just don’t have the knowledge necessary to determine whether any of this is old or new, theoretical or applicable, possible or even feasible, or merely a bunch of garbage. I had actually convinced myself one time that I had independently posited the existence of multiplicative calculi, but boy was I saddened to find out that it had already been around for some time. So I’m looking to this community in the hopes that a few of you might share your knowledge in this area.

From what I understand, today's digital computers rely on transistors, which in turn act as switches that relay two possible states, that is, on or off. Based on this, we know that at their most basic level, computers understand sequences of bits which represent instructions or operations for the processor to perform. Now, what if there was a way to relay that information in a much faster way?

Note: The explanation I’m using to model the inner workings of an atomic computer uses 2 atoms, but could use any arrangement of 1 or more particles that aren’t necessarily atoms. I also make a fair amount of assumptions about the data we can gather from them.

First, suppose we have an enclosure which consists of two atoms—in this case Hydrogen, whose diameter is roughly 50 picometers (50×10-12 m)—sitting side by side so we can say they're almost touching. Also suppose we can determine almost instantly whether the two atoms are close enough. Then, let this represent a state of on or 1.

Next, suppose we can generate a field or force ##\vec{F}## that will displace a (possibly charged) Hydrogen atom a sufficient distance away so that we may similarly call this state off or 0.

Finally, suppose we can vary the ##\vec{F}## field/force such that the Hydrogen atom moves back to its initial on position. This completes an entire cycle for which there are only two possible states.

For posterity and simplicity, let's suppose we can accelerate these atoms at or near the speed of light. From this, we shall calculate the frequency at which this machine can process individual bits of information.

$$

c \; = 3 \times 10^8 \; \mathrm{m/s} = 3 \times 10^{20} \; \mathrm{pm/s} \\

d \, = 50 \; \mathrm{pm} \\

f = \dfrac{c}{d}

= \dfrac{3 \times 10^{20} \; \mathrm{pm/s}}{50 \; \mathrm{pm}}

= 6 \times 10^{18} \; s^{-1} \; \mathrm{or} \; 6\times10^{18} \; \mathrm{bits/s} \\

\ \ = \mathrm{5.5 \; million \; terabits/s \;\; or \;\; 700 \; thousand \; terabytes/s}

$$

For a more real-world estimate, 1% of the speed of light would just be 1% of the final frequency, which would still result in roughly 7 thousand terabytes/s. As I mentioned before, this still presents a significant improvement over today's technology.c \; = 3 \times 10^8 \; \mathrm{m/s} = 3 \times 10^{20} \; \mathrm{pm/s} \\

d \, = 50 \; \mathrm{pm} \\

f = \dfrac{c}{d}

= \dfrac{3 \times 10^{20} \; \mathrm{pm/s}}{50 \; \mathrm{pm}}

= 6 \times 10^{18} \; s^{-1} \; \mathrm{or} \; 6\times10^{18} \; \mathrm{bits/s} \\

\ \ = \mathrm{5.5 \; million \; terabits/s \;\; or \;\; 700 \; thousand \; terabytes/s}

$$

Perhaps one day we'll reach the conclusion that a system with two possible states is surely the simplest one, but probably not the most efficient one. Indeed, the ability to represent information in more states than 2 can lead to an exponential rise in the amount of information we can gather and process at any given time. In light of this, also consider the possibility that the atoms in this design could represent numerous different states, then data could be ascertained about their atomic states and transmitted in much larger segments at any given time. Examples of information that could be used to represent multiple states include charge distribution, attraction/repulsion and distance, among others. It's also understood that working at the atomic level introduces issues of accuracy and precision; however, by establishing an absolute minimum and maximum that are well within a proven range of tolerance for the data we can gather, and scaling it down to a finite number of states, we can drastically reduce the possibility for error.

Clearly though, the premise behind quantum computers holds the most benefit by far, but the field is still very young. Although atomic computers would never supplant quantum computers, it could very well produce more tangible, short-term benefits over today's technology. A joke at the expense of quantum computers: The quantum superposition principle as it’s applied to quantum computing is quite appealing from a computer scientist's point of view; that is, sorting algorithms can now assume that data must already be in sorted order (since it can exist in all of its possible states simultaneously), therefore no sort is needed. The problem only arises when we actually try looking at it…

But getting back to the reason I created this post, I really enjoy thinking about these kinds of things, but many times I just don’t have the knowledge necessary to determine whether any of this is old or new, theoretical or applicable, possible or even feasible, or merely a bunch of garbage. I had actually convinced myself one time that I had independently posited the existence of multiplicative calculi, but boy was I saddened to find out that it had already been around for some time. So I’m looking to this community in the hopes that a few of you might share your knowledge in this area.