- #1

mente oscura

- 168

- 0

Hello.

[tex]Let \ T \in{N} \ / \ T=odd[/tex]

Prove:

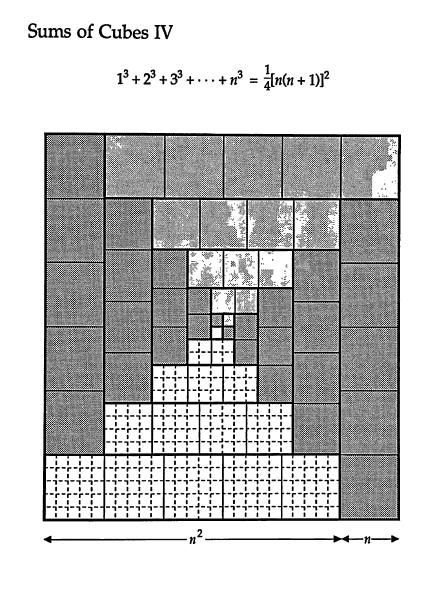

[tex]1^3+3^3+5^3+7^3+ ... +T^3=\dfrac{[T(T+2)]^2-1}{8}[/tex]

Regards.

[tex]Let \ T \in{N} \ / \ T=odd[/tex]

Prove:

[tex]1^3+3^3+5^3+7^3+ ... +T^3=\dfrac{[T(T+2)]^2-1}{8}[/tex]

Regards.