JD_PM

- 1,125

- 156

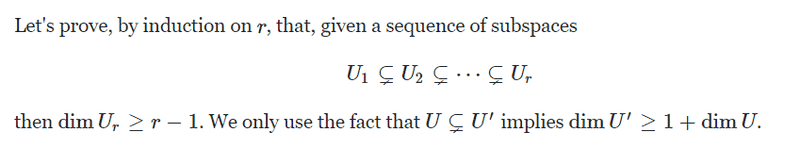

Summary:: I want to understand the following theorem and its proof (which can be found in MSE, link below): Let ##V## be a ##n##-dimensional vector space, let ##U_i \subseteq V## be subspaces of ##V## for ##i = 1,2,\dots,r## where $$U_1 \subseteq U_2 \subseteq \dots \subseteq U_r$$

If ##r>n+1## then there exists an ##i<r## for which ##U_i = U_{i+1}=\dots=U_r##

I understand that if the subspaces were to be strictly contained (i.e. no possibility of equality between them) then, when going from ##U_i## to ##U_{i+1}##, the dimension of the subspace would increase by one. Hence, when reaching ##U_r## the dimension would be greater than ##n+1##. However, this is not possible since ##U_r## is a subspace of ##V## and thus has dimension at most ##n##.

My issues are

1) I do not see why ##\dim U_r>\dim U_i+r-1## follows from the above argument

2) This is related to 1). I do not see why MSE user egreg here assumes non-equality of the subspaces

I appreciate your guidance!

If ##r>n+1## then there exists an ##i<r## for which ##U_i = U_{i+1}=\dots=U_r##

I understand that if the subspaces were to be strictly contained (i.e. no possibility of equality between them) then, when going from ##U_i## to ##U_{i+1}##, the dimension of the subspace would increase by one. Hence, when reaching ##U_r## the dimension would be greater than ##n+1##. However, this is not possible since ##U_r## is a subspace of ##V## and thus has dimension at most ##n##.

My issues are

1) I do not see why ##\dim U_r>\dim U_i+r-1## follows from the above argument

2) This is related to 1). I do not see why MSE user egreg here assumes non-equality of the subspaces

I appreciate your guidance!