- #1

mitleid

- 56

- 1

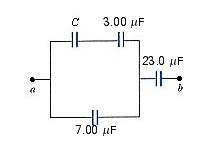

Four capacitors are connected as shown in the figure below (C = 16 mF)

(a) Find the equivalent capacitance between points a and b.

(b) If V(ab) = 16.5 V, calculate the charge on the the 23.0 mF capacitor.

This is repeated for each capacitor in the circuit.

For the sake of simplicity, C = 16mF, C1 = 3 mF, C2 = 7 mF and C3 = 23 mF

I've correctly answered the first two parts of the problem. First C and C1 are considered in series and so the equivalent capacitance is found as:

1/C' = 1/C + 1/C1

C' and C2 are in parallel, so their equivalent capacitance C'' = C' + C2

Finally, C'' and C3 are in series, and the same equation as above is applied to get 6.74 mF.

To get the charge on C3, the value for total C (6.74) is used in the equation Q = CV to get 111 mC.

Solving for the other three capacitors has proved difficult... most likely I am making a similar mistake for both parts (since the charge for C and C1 are identical I only have two charges left to find).

To find the charge on C2 (7 mF), it seems I should be able to just multiply its capacitance by the voltage since it is in parallel (and so Q is directly proportional to each C).

Any advice?

(a) Find the equivalent capacitance between points a and b.

(b) If V(ab) = 16.5 V, calculate the charge on the the 23.0 mF capacitor.

This is repeated for each capacitor in the circuit.

For the sake of simplicity, C = 16mF, C1 = 3 mF, C2 = 7 mF and C3 = 23 mF

I've correctly answered the first two parts of the problem. First C and C1 are considered in series and so the equivalent capacitance is found as:

1/C' = 1/C + 1/C1

C' and C2 are in parallel, so their equivalent capacitance C'' = C' + C2

Finally, C'' and C3 are in series, and the same equation as above is applied to get 6.74 mF.

To get the charge on C3, the value for total C (6.74) is used in the equation Q = CV to get 111 mC.

Solving for the other three capacitors has proved difficult... most likely I am making a similar mistake for both parts (since the charge for C and C1 are identical I only have two charges left to find).

To find the charge on C2 (7 mF), it seems I should be able to just multiply its capacitance by the voltage since it is in parallel (and so Q is directly proportional to each C).

Any advice?

Last edited: