chiyu said:

But let's say instead of a circle, we take the surface of a oblong cylinder, then depending on the angle the distance will change right?

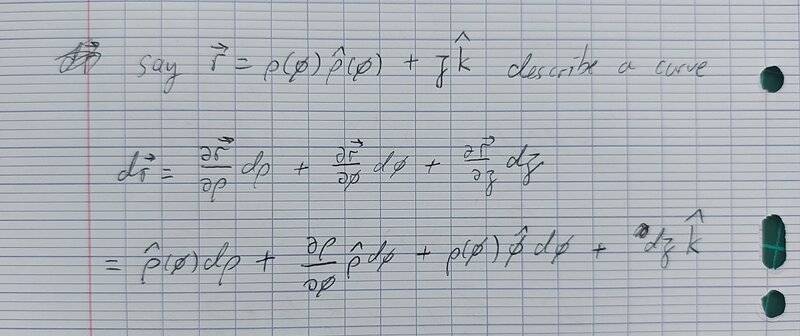

You are confusing the general expression of a directed element ##d\mathbf{ r}## with a specific directed element subject to constraints for doing a specific line integral. Let me show you what I mean. Say you have a vector field $$\mathbf{E}=E_{\rho}(\rho,\phi,z)\hat {\rho}+E_{\phi}(\rho,\phi,z)\hat {\phi}+E_z(\rho,\phi,z)\hat {z}.$$In this expression, coordinates ##\rho##, ##\phi## and ##z## are placeholders for

any radial distance ##\rho##,

any polar angle ##\phi## and

any axial distance ##z##. They are completely independent of each other and the field doesn't give a hoot whether you want to do a line integral along a circle or an ellipse or a squiggle. It is what it is. Likewise the directed element ##d\mathbf{r}## is, as has already been said, is

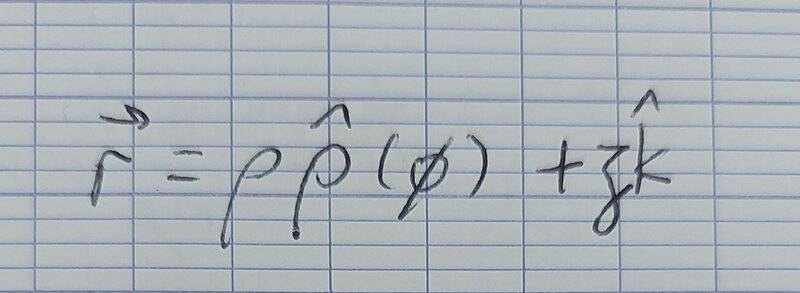

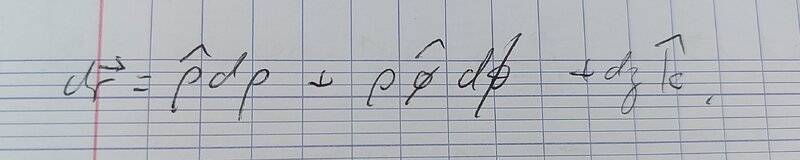

always $$d\mathbf{r}=d\rho~\hat{\rho}+\rho~d\phi~\hat{\phi}+dz~\hat z.$$It follows that the integrand of a line integral in cylindrical coordinates is $$\begin{align}\mathbf{E}\cdot d\mathbf{r} & =[E_{\rho}(\rho,\phi,z)\hat {\rho}+E_{\phi}(\rho,\phi,z)\hat {\phi}+E_z(\rho,\phi,z)\hat {z}]\cdot (d\rho~\hat{\rho}+\rho~d\phi~\hat{\phi}+dz~\hat z)\nonumber \\

&= E_{\rho}(\rho,\phi,z)d\rho+E_{\phi}(\rho,\phi,z)\rho~d\phi+E_z(\rho,\phi,z)dz \nonumber \\

\end{align}.$$The above expression is

always the integrand of a line integral regardless of the shape of the line you are integrating over. I repeat once more that ##r##, ##\phi## and ##z## are independent coordinates which means that the partial derivative of one with respect to another is zero.

Now how do you set up a specific line integral? Say you want to do a line integral in the xy-plane along a circle of radius ##R## from ##\phi_1## to ##\phi_2##. The equation of a circle in cylindrical coordinates in the xy-plane is ##\rho=R##, ##d\rho=0## and ##z=dz=0.## With these replacements, the integrand becomes

$$\mathbf{E}\cdot d\mathbf{r} = E_{\phi}(R,\phi,0)R~d\phi$$and you have to integrate from ##\phi_1## to ##\phi_2.##

Now say you want to do a line integral along an ellipse of semi-major axis ##a## and eccentricity ##e##. The equation of this ellipse in cylindrical coordinates in the xy plane is $$\rho(\phi)=\frac{a(1-e^2)}{1+e\cos\phi}\implies d\rho=\frac{ae(1-e^2)\sin\phi}{(1+e\cos\phi)^2}d\phi$$ and, of course ##z=dz=0.## Then $$\mathbf{E}\cdot d\mathbf{r}=E_{\rho}(\rho(\phi),\phi,0)\frac{ae(1-e^2)\sin\phi}{(1+e\cos\phi)^2}d\phi+E_{\phi}(\rho(\phi),\phi,0)\rho(\phi)~d\phi$$and you have to integrate from ##\phi_1## to ##\phi_2.##

To summarize, the

general expression for a directed element is

$$d\mathbf{r}=d\rho~\hat{\rho}+\rho~d\phi~\hat{\phi}+dz~\hat z.$$ The

specific directed element along a circle in the xy-plane is $$d\mathbf{r}=\rho~d\phi~\hat{\phi}.$$The

specific directed element along an ellipse in the xy-plane is $$d\mathbf{r}=\frac{a(1-e^2)}{1+e\cos\phi}\left[\frac{e\sin\phi}{(1+e\cos\phi)}~\hat{\rho}+\hat{\phi}\right]d\phi.$$Do you see how it works?

.

.