Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

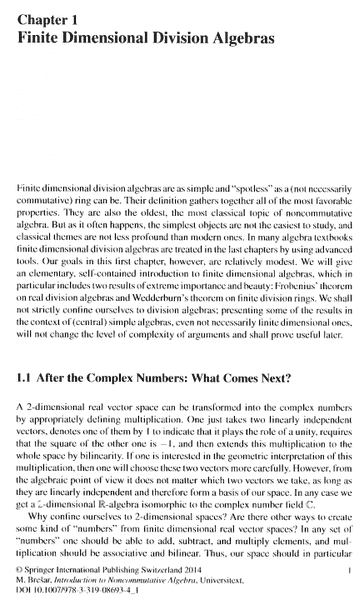

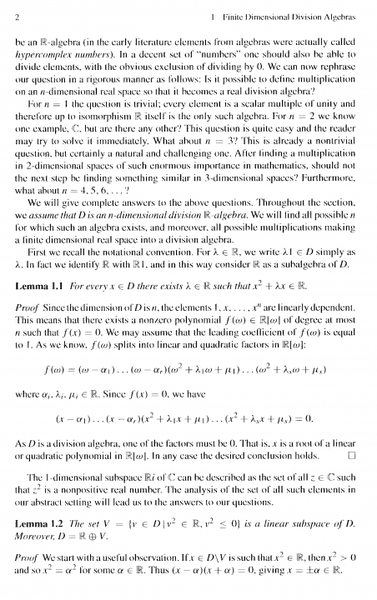

I am reading Matej Bresar's book, "Introduction to Noncommutative Algebra" and am currently focussed on Chapter 1: Finite Dimensional Division Algebras ... ...

I need help with some aspects of the proof of Lemma 1.3 ... ...

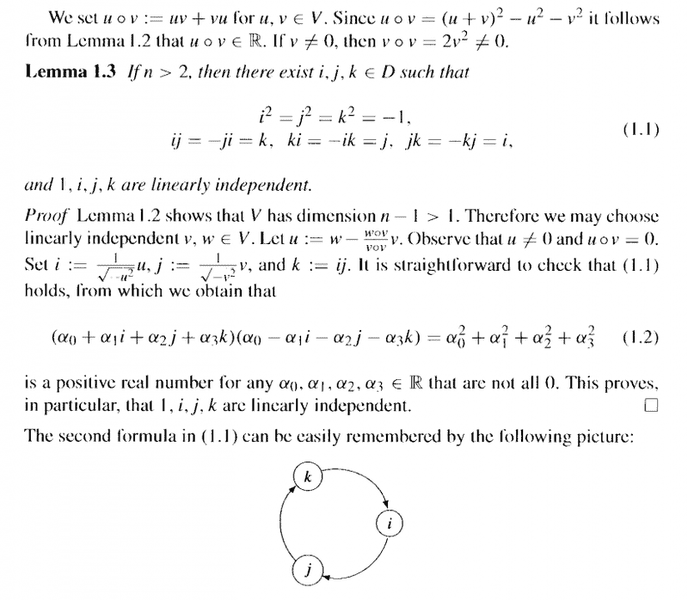

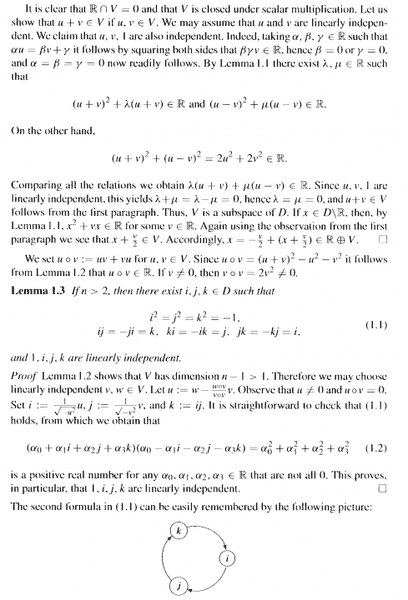

Lemma 1.3 reads as follows:

In the above text by Matej Bresar we read the following:

" ... ... Set ##i := \frac{1}{ \sqrt{ -u^2 } } u , \ \ j := \frac{1}{ \sqrt{ -v^2 } } v## , and ##k := ij##.

It is straightforward to check that (1.1) holds ... ... "

I need some help in proving that ##ij = -ji = k## ... sadly I cannot get past the point of substituting the relevant formulas ...

Hope someone can help ...Peter

EDIT ... I must admit that as I reflect further on Lemma 1.3 I am more confused than I first thought ... why is Bresar defining another 'multiplication' in V ... that is why define ##\circ## ... we already have a multiplication from D ... and how does the new definition ##\circ## play out when validating 1.1 ...============================================================================

In order for readers of the above post to appreciate the context of the post I am

providing pages 1-3 of Bresar ... as follows ...

I need help with some aspects of the proof of Lemma 1.3 ... ...

Lemma 1.3 reads as follows:

In the above text by Matej Bresar we read the following:

" ... ... Set ##i := \frac{1}{ \sqrt{ -u^2 } } u , \ \ j := \frac{1}{ \sqrt{ -v^2 } } v## , and ##k := ij##.

It is straightforward to check that (1.1) holds ... ... "

I need some help in proving that ##ij = -ji = k## ... sadly I cannot get past the point of substituting the relevant formulas ...

Hope someone can help ...Peter

EDIT ... I must admit that as I reflect further on Lemma 1.3 I am more confused than I first thought ... why is Bresar defining another 'multiplication' in V ... that is why define ##\circ## ... we already have a multiplication from D ... and how does the new definition ##\circ## play out when validating 1.1 ...============================================================================

In order for readers of the above post to appreciate the context of the post I am

providing pages 1-3 of Bresar ... as follows ...

Attachments

Last edited: