member 731016

- Homework Statement

- Please see below

- Relevant Equations

- Please see below

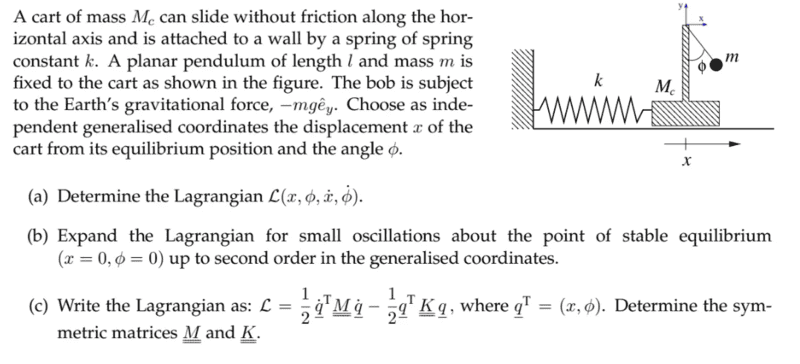

For this problem,

My working for (c) is

##

\begin{aligned}

& L=\frac{1}{2} M \dot{x}^2+\frac{1}{2} m\left(x^2+2 \dot{x} l \dot{\phi} \cos \phi+l^2 \dot{\phi}^2\right)+m g l \cos \phi-\frac{1}{2} k x^2 \\

\end{aligned}

##

##L =\frac{1}{2} M \dot{x}^2+\frac{1}{2} m\left(\dot{x}^2+2 \dot{x} l \dot{\phi}-\dot{x} l \dot{\phi} {\phi}^2+l^2 \dot{\phi}^2\right)+m g l-\frac{m g l \phi^2}{2}-\frac{1}{2} k x^2## using small angle approximation for cosine.

Then taking partial deratives for the Lagrange equation of phi and x.

I get the following equations

\begin{aligned}

& \left(m l-\frac{1}{2} m l \phi^2\right) \ddot{x}+m l^2 \ddot{\phi}=-m g l \phi \\

& (M+m) \ddot{x}+\left(m l-\frac{1}{2} m l \phi^2\right) \ddot{\phi}=-k x+m l \dot{\phi}^2 \phi \\

&

\end{aligned}

Then writing the equations in matrix form ##M \ddot{x} = -kx##, I cannot find a symmetric matrix for K. Only for M.

Does anybody please agree that the problem has a mistake that it is impossible for find a symmetric matrix for K?

Thanks!

My working for (c) is

##

\begin{aligned}

& L=\frac{1}{2} M \dot{x}^2+\frac{1}{2} m\left(x^2+2 \dot{x} l \dot{\phi} \cos \phi+l^2 \dot{\phi}^2\right)+m g l \cos \phi-\frac{1}{2} k x^2 \\

\end{aligned}

##

##L =\frac{1}{2} M \dot{x}^2+\frac{1}{2} m\left(\dot{x}^2+2 \dot{x} l \dot{\phi}-\dot{x} l \dot{\phi} {\phi}^2+l^2 \dot{\phi}^2\right)+m g l-\frac{m g l \phi^2}{2}-\frac{1}{2} k x^2## using small angle approximation for cosine.

Then taking partial deratives for the Lagrange equation of phi and x.

I get the following equations

\begin{aligned}

& \left(m l-\frac{1}{2} m l \phi^2\right) \ddot{x}+m l^2 \ddot{\phi}=-m g l \phi \\

& (M+m) \ddot{x}+\left(m l-\frac{1}{2} m l \phi^2\right) \ddot{\phi}=-k x+m l \dot{\phi}^2 \phi \\

&

\end{aligned}

Then writing the equations in matrix form ##M \ddot{x} = -kx##, I cannot find a symmetric matrix for K. Only for M.

Does anybody please agree that the problem has a mistake that it is impossible for find a symmetric matrix for K?

Thanks!