BWV

- 1,583

- 1,936

This Nature paper that attempts to quantify diminishing returns from scientific research across a wide range of fields is getting a fair amount of press.

My initial take was just a 'low hanging fruit' argument where all the 'easy' discoveries have been made. The authors argue against that, citing the uniformity of the decline as evidence against, but I don't find that argument compelling. ISTM that diminishing returns / low hanging fruit in physics can coexist with the splintering, due to complexity, of real advances in biology that nevertheless aren't considered 'revolutionary' as non specialists dont understand them.

My initial take was just a 'low hanging fruit' argument where all the 'easy' discoveries have been made. The authors argue against that, citing the uniformity of the decline as evidence against, but I don't find that argument compelling. ISTM that diminishing returns / low hanging fruit in physics can coexist with the splintering, due to complexity, of real advances in biology that nevertheless aren't considered 'revolutionary' as non specialists dont understand them.

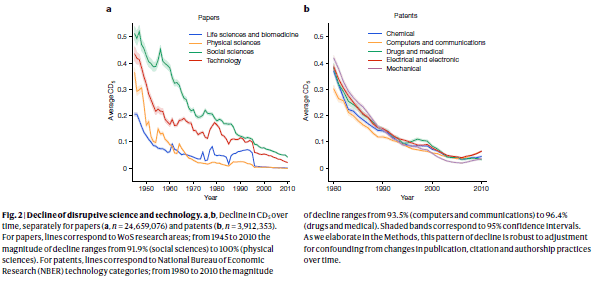

Theories of scientific and technological change view discovery and invention as endogenous processes1,2, wherein previous accumulated knowledge enables future progress by allowing researchers to, in Newton’s words, ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’3,4,5,6,7. Recent decades have witnessed exponential growth in the volume of new scientific and technological knowledge, thereby creating conditions that should be ripe for major advances8,9. Yet contrary to this view, studies suggest that progress is slowing in several major fields10,11. Here, we analyse these claims at scale across six decades, using data on 45 million papers and 3.9 million patents from six large-scale datasets, together with a new quantitative metric—the CD index12—that characterizes how papers and patents change networks of citations in science and technology. We find that papers and patents are increasingly less likely to break with the past in ways that push science and technology in new directions. This pattern holds universally across fields and is robust across multiple different citation- and text-based metrics1,13,14,15,16,17. Subsequently, we link this decline in disruptiveness to a narrowing in the use of previous knowledge, allowing us to reconcile the patterns we observe with the ‘shoulders of giants’ view. We find that the observed declines are unlikely to be driven by changes in the quality of published science, citation practices or field-specific factors. Overall, our results suggest that slowing rates of disruption may reflect a fundamental shift in the nature of science and technology.