Trying2Learn

- 375

- 57

- TL;DR Summary

- How does my brain perceive light?

I approach a traffic light. It is red.

I know it is a light.

What is happening in my brain to inform me that I am looking at a red light, and not a brightly colored red circle on the canvas of my perceptions of the physical world?

If my eyes are moist and I squint, I see radiating red lines and that sort of informs me it light, since even a brightly colored red dot will not emit such rays. But that is based on prior experience with such objects. If I did not squint, how would I know it is light.

One could say that nearby objects are slightly tinted with red light and that is how I know it. But I could paint a similar scene and tint the nearby colors slightly red.

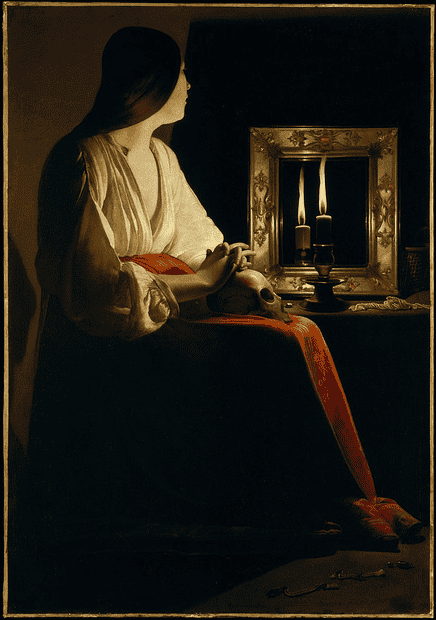

Here is a painting by La Tour. I ALMOST see the candle as a source of electromagnetic radiation (almost); so there is definitely a skill of artistic replication involved.

In any case, how do I know I am looking at a source of electromagnetic waves at a stop light, and not a white-specular red painted circle? How does my brain inform me that the candle below is not emitting electromagnetic waves (and I am ONLY seeing reflected white light from the area of the candle in the dark canvas. What is happening in my brain to inform me that I am looking at a source of light?

I know it is a light.

What is happening in my brain to inform me that I am looking at a red light, and not a brightly colored red circle on the canvas of my perceptions of the physical world?

If my eyes are moist and I squint, I see radiating red lines and that sort of informs me it light, since even a brightly colored red dot will not emit such rays. But that is based on prior experience with such objects. If I did not squint, how would I know it is light.

One could say that nearby objects are slightly tinted with red light and that is how I know it. But I could paint a similar scene and tint the nearby colors slightly red.

Here is a painting by La Tour. I ALMOST see the candle as a source of electromagnetic radiation (almost); so there is definitely a skill of artistic replication involved.

In any case, how do I know I am looking at a source of electromagnetic waves at a stop light, and not a white-specular red painted circle? How does my brain inform me that the candle below is not emitting electromagnetic waves (and I am ONLY seeing reflected white light from the area of the candle in the dark canvas. What is happening in my brain to inform me that I am looking at a source of light?